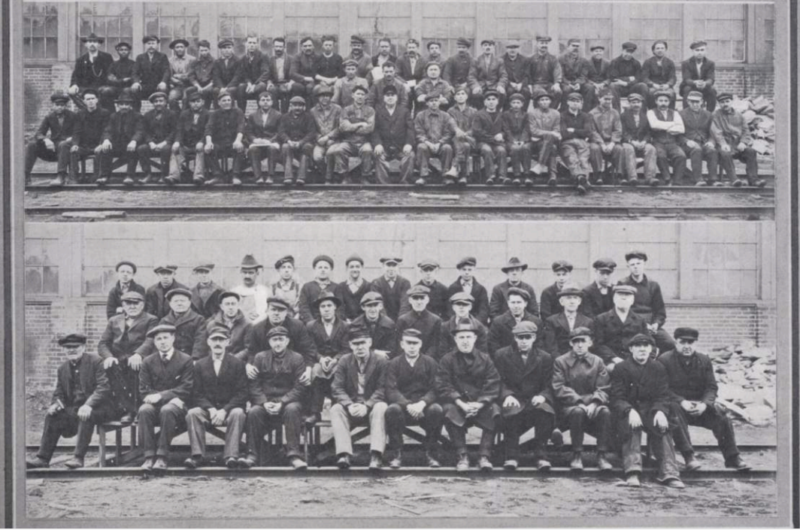

WATERTOWN — On June 16, Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archive delved into the world of Whitinsville, a small town in central Massachusetts with one of the oldest Armenian communities in the state. This presentation was cosponsored by the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research and the Armenian Cultural Center.

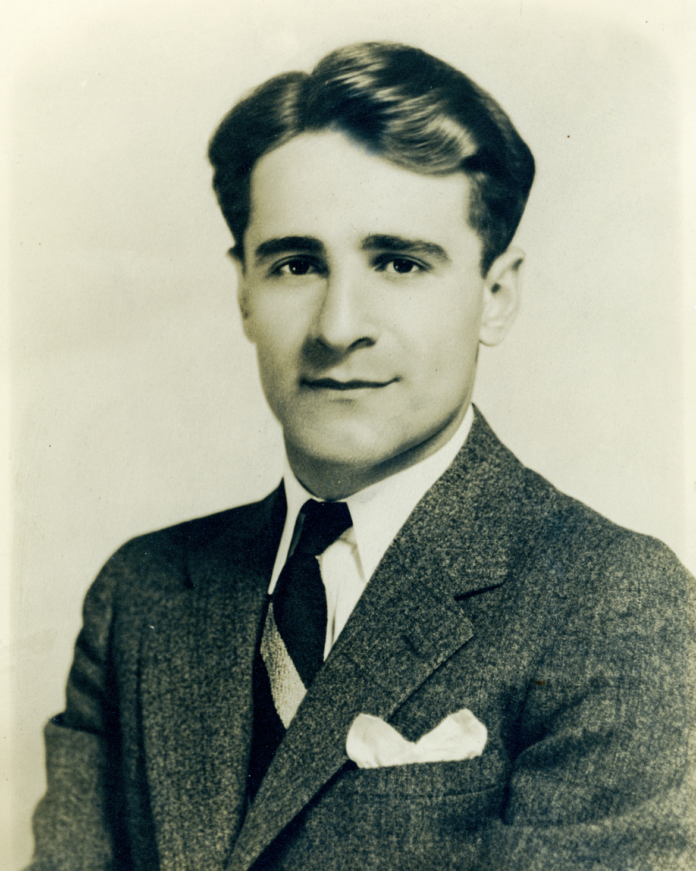

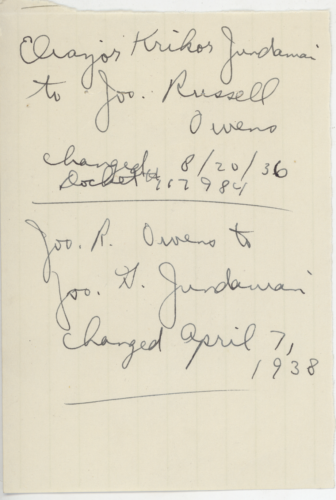

Armenians of Whitinsville (armeniansofwhitinsville.org), a digital archive that documents the history of Armenians in this town, was represented by Greg Jundanian and Lisa Misakian, two of the handful of co-founders of the project.

“The Jundanian family, originally from Parchanj, a town located in the Kharpert province of the Armenia plateau, immigrated to the United States before 1915 settled and in Whitinsville in the 1920s. Misakian’s family has roots in Whitinsville since the 1880s, when her grandfather first arrived from Parchanj.

Arto Vaun, the Executive Director of Project SAVE, explained how Whitinsville is a part of the Armenian diasporan experience while Jundanian and Misakian shared their recent documentation work.

The archive developed out of conversations between Jundanian and Jeff Kalousdian in spring 2021. They proposed it to the Whitinsville community through the local Surp Asdvadzadzin Armenian Church’s electronic newsletter, which introduced Misakian to the project.

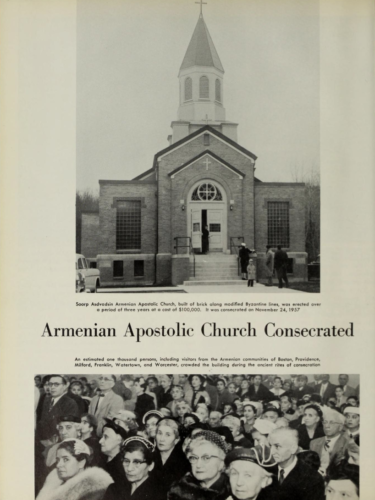

Jundanian explained the mission of the archive, declaring “It is a digital archive that pays respects to those before us. It is about the past but also about putting together something for future generations.” The project is similar to that of a houshamadyan, or an Armenian memory book that compatriotic societies used to publish on their places of origin after the Armenian Genocide, and it has gained further support since it first started. Its financial sponsor is the American Cultural Association of America. Although the archive project has no official affiliation with Soorp Asdvadzadzin, it is also supported by the church. The church announces the project’s activities on its weekly Friday electronic bulletin using its national email list, promotes the project on Sundays when possible, provides contact information in order for the project to arrange interviews, and offers photos and articles pertaining to the church for the website’s use.