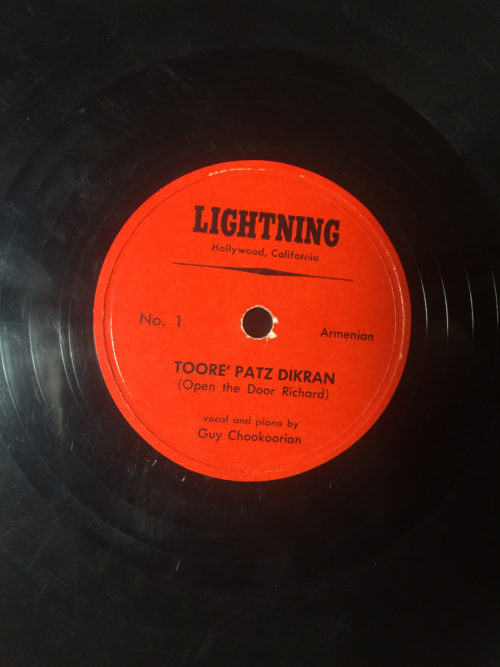

LOS ANGELES — The year is 1947. The location, a hotel somewhere in the Eastern United States where an Armenian youth convention is being held. A group of young people are gathered in a room having a little after-hours party; the day’s meetings, banquets, and dance have ended. Someone brings out a portable record player. The group’s jokester, with a sly smile, pulls a record out. “You guys gotta hear this,” he says. As the shellac disc begins to spin at 78 rpms, a beautiful piano melody flows from the tiny speaker. The one young lady in the room who is a classical music snob is pleasantly surprised. Then the pianist suddenly shifts to a jump-blues riff. There is confusion in the room as to what they are listening to. The jokester is grinning. And then the voice on the record, that of a young man their own age, singing jukebox music in Armenian starts to belt out:

Toore patz, Dikran

Toore patz, vor yes ners kam

Toore patz, Dikran

Dikran, inchoo toore ches panar?