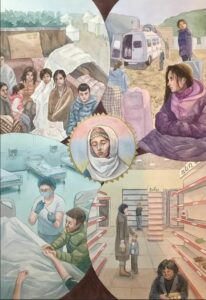

YEREVAN — As the latest chapter of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict enters its fourth week, it takes a heavy toll on its participants. Estimates of casualties sustained during the conflict vary wildly, with conservative estimates pegging it as low as two thousand, whilst some claims put the number as high as five thousand. Another toll the conflict has taken is in the form of displaced peoples. As many as 75,000 refugees, nearly 90 percent of Artsakh’s population of women and children, have been forced to leave their homes, whether they be in border towns such as Martakert or comparatively safer cities such as Stepanakert.

In addition to those that took refuge in Armenian cities on the Artsakh border such as Goris and Vardenis, many have also made their way to Yerevan. These beleaguered families have been readily hosted by the city’s hotels, by relatives, by charitable organizations, and even by strangers. One of these families is that of Gayane S. As a Stepanakert resident, Gayane was in the thick of the heavy enemy shelling and UAV attacks on the first days of the war and was forced to flee.

In the wake of a surprise attack in which the Azeris launched swarms of drones against Artsakh, the women and children of this family found themselves in Yerevan. They were forced to leave behind their male relatives who went straight to the front. Happily, this beleaguered family has found shelter in the home of a very generous friend in Yerevan, and Gayane has been residing in a compound in Armenia’s capital city ever since.

Gayane, 37, vividly remembers the day her life changed forever: “Early in the morning, we heard thunder from the clear skies, and we understood that these are the sounds of war. My husband immediately spotted an Azeri UAV being shot down.”

Gayane was quick to wake her children and lead them to the bunker in their home’s garden. The bunker had been constructed during the fighting of the 1990s, and Gayane’s family had opted to keep it intact when they bought their residence in downtown Stepanakert: “Our neighbors were quite happy with that decision. They came to the bunker when the bombardment started.” Gayane, along with her daughter, Anna, and her neighbors prayed as the boom of guns continued.

However, the bunker was small and damp, its walls made of sand. Soon, Gayane’s children complained of nausea, and they could not stay in the bunker. As the air raid sirens continued to blare, the bunker shook as Artsakh’s howitzers fired in retaliation. When Gayane’s husband told her to prepare to leave the city with her children, she never imagined she would be gone long. “I was sure we would come back soon. We had tracked dirt into the house from the bunker, and I was sure we would be back soon to clean it all up,” she added. But as the weeks came and went, the prospect for the Gayane’s quick return to their home became grim.