BELMONT, Mass. – When Armenians from outside Armenia come to visit, they seldom have occasion to see anything outside of the capital city of Yerevan, and if they do go elsewhere it is usually to the other cities and noteworthy touristic destinations. They drive straight through the villages, without much time to do more than glance at their worn-out state. Tamara Stepanyan’s documentary film, “Village of Women [Kanants Gyughe],” rectifies this a little.

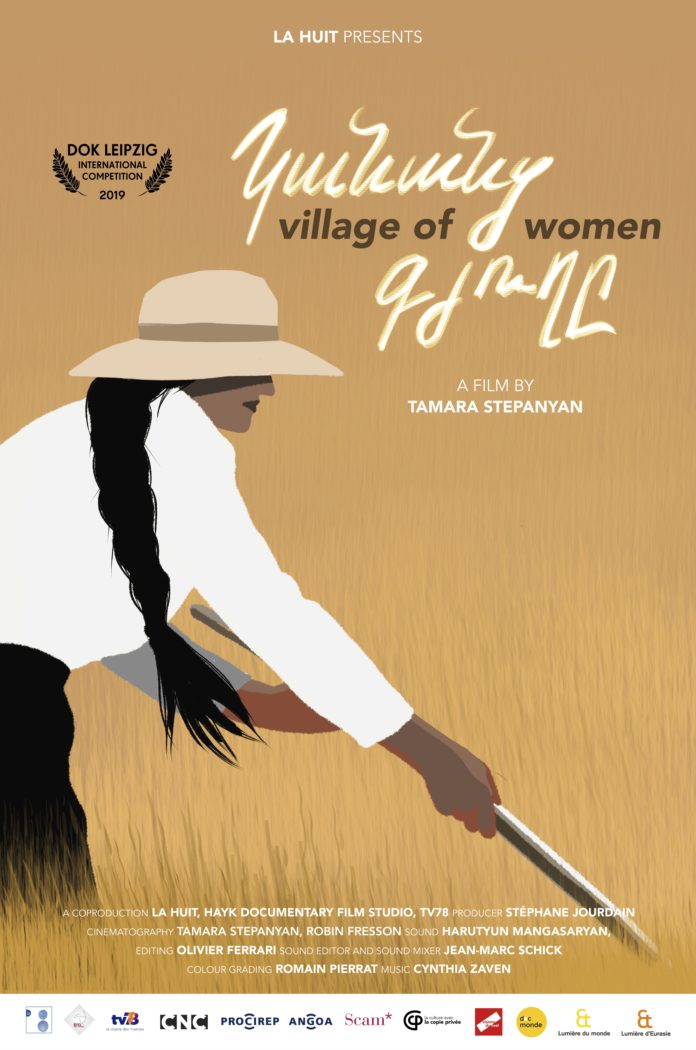

A new film, it is just starting to garner attention. “Village of Women” was one of 11 films chosen out of 3,000 to be presented at DOK Leipzig, the International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film – one of the oldest film festivals in the world – in 2019, and is now traveling throughout the film world. It will be shown in Belmont’s Global Cinema Film Festival of Boston on Sunday, March 22 at 6 p.m. at Studio Cinema (376 Trapelo Road, Belmont, https://www.eventbrite.com/e/global-cinema-film-festival-of-boston-tickets-91132524835).

The beautifully filmed documentary is set in Lichk, a village 130 kilometers distant from Yerevan. Lichk is located in Gegharkunik Province, south of Lake Sevan, and has a population officially of 5,430. The majority of the adult men leave the village to go work in Russia for eight or nine months out of the year, primarily to do manual labor in fields like construction. Boys there turn 18, go into the army for two years, and then immediately begin this cycle of seasonal work, without pursuing any further education. Life in Lichk seems like life in a third-world country, with no factories or work. Houses are worn-out and women always seem tired. They do heavy physical agricultural labor, keep the cattle, and maintain their families while men send back money occasionally and call over the phone until their annual winter break. However, the women also find occasional consolation from their difficult lives through song, dance and conversation.

Stepanyan, born in Soviet Armenia, moved to Lebanon as a child and then to France, where she lives now and has become an accomplished cinematographer (see “Exile and Waiting Transformed into Film through the Work of Tamara Stepanyan,” https://mirrorspectator.com/2018/02/19/exile-waiting-transformed-film-work-tamara-stepanyan/). Several years ago, she said that she noticed while reading newspapers that the villages in Gegharkunik were emptied of men. It happens that she goes every year to see her parents in Armenia on vacation. While in Armenia with her husband in the summer, she decided to take a taxi to investigate.

The driver knew the region and suggested several places. They came to Lichk through its narrow streets and stopped at the post office, which seemed like a central place. Local children immediately came and surrounded her, asking what she wanted and asking her to come with them. She said yes, Stepanyan related, and went with one, ending up at the home of Anush Oseyan. Anush invited her to drink coffee, and thus it all began by chance. It could have been a neighboring village, Stepanyan said.

They spent the whole day there, and returned to Yerevan in the evening. Stepanyan kept ties via telephone. And every time she went to Yerevan she would also go to Lichk to visit Anush. Stepanyan said, “First it was necessary to establish all the relationships slowly, from the very beginning, so that there is a state of confidence. If there is no confidence, especially in documentary films, you cannot work.” This particular situation, Stepanyan noted, was a very sensitive one. She said, “You reach a place where an Armenian woman is very proud. She does not want you to see her family in pain or weakness. She always wants you to see her family in good form. Even when the men were not present, the women in a very beautiful way preserved the family.”