By Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

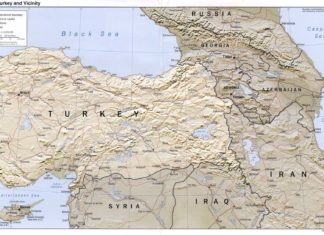

A scandal erupted in mid-June and marred an exhibit in Paris at UNESCO which featured traditional stone crosses from Armenian church architecture known as Khachkars. These unique sculptures and reliefs had been included in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in November 2010.(1) The exhibit, co-sponsored by the Republic of Armenia’s Culture Ministry and inaugurated in the presence of numerous diplomats, artists, historians, and clergy, would have celebrated a magnificent tribute to the Khachkar tradition had it not been for the fact that at the last minute UNESCO erased all mention of where the stone crosses featured in photographs were to be found. The explanation for the elimination of the place names locating the pieces, as well as of a huge map of historic Armenia designating those locations, was that, since the Khachkars were not all on the territory of the Republic of Armenia , but could also be found in present-day Azerbaijan and Turkey , it would be better to maintain silence.

But, there is no way to maintain silence: “The stones will cry out.” And they did. Representatives of the Collectif VAN (Vigilance Armenienne contre le Negationnisme), present at the opening, protested with an open letter to Irina Bokova, Director General of UNESCO. (2) In the letter, they argued that not only does it violate academic practice to fail to mention the location of art works in such an exhibit, but, by ignoring their location, the exhibitors were rendering themselves complicit in a wild distortion of the historical record. To ignore the place names is to conceal the historical presence of the Armenian people and civilization in that vast region.

Travellers through eastern Anatolia and present-day Azerbaijan will find some Khachkars in their places of origin – although thousands have been deliberately destroyed — and will make the historical connection.(3) It is not only the beautiful stone crosses but the wealth of religious monuments — be they chapels, churches, cathedrals, or monasteries – populating that geographical region that bear testimony to the physical and cultural presence of Christian Armenians since the fourth century. As Italian art historian Arpago Novello identified, this religious art was an integral part of the Armenians’ identity. “The Armenians’ tenacious attachment to the Christian religion,” he wrote,” testified by the thousands of crosses erected or sculpted almost everywhere and for every occasion, and by the extraordinary wealth of sacred buildings, was not merely a spiritual matter but a prime feature of their very identity and a symbol of their physical survival.”(4)

Yet that very presence is subject to denial and distortion. My brother, my husband, and I experienced this during a journey through eastern Anatolia in May. In place of the historical record we encountered mythology, with its own personages, events, and causality. In this mythological landscape, we were not in historic Armenia, let alone Western Armenia, but in eastern Turkey, in one of the Anatolian provinces, and everything we might have expected to recognize from past historical accounts had disappeared or had been transformed into something else, often into its very opposite.

We were travelling as part of a small group of Armenian Americans who sought to retrace the steps of parents and ancestors, to visit their villages and towns where they were born and lived before the genocide. It was like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. We had scattered pieces from our parents, like names of villages, descriptions of some localities, and we had read the accounts of eye-witnesses to the Genocide, like Johannes Lepsius, Jakob Künzler, Ambassador Henry Morgenthau, and others. But when we looked at a present-day map of Turkey , we more often than not found nothing resembling the place names. Our German guide book did not offer much help.