During the victory parade in Baku on December 10, 2020, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey stood on the dais as a hero next to Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev, as he extolled the memory of Enver Pasha, one of the planners of the Armenian Genocide, and declared, “We are here to realize the dreams of our ancestors,” meaning to bring the century-old genocidal policy to its logical conclusion.

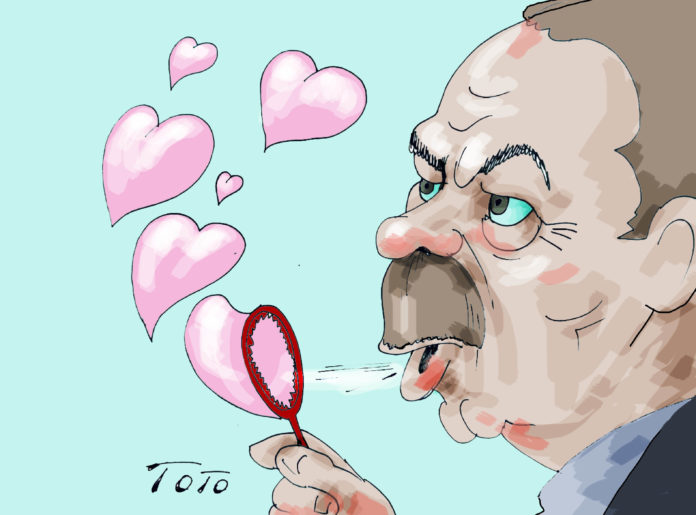

Today, Mr. Erdogan wishes to project a different, more benevolent image, that of a peacemaker. Some of his friends have even suggested he should be considered for a Nobel Peace Prize.

Has Mr. Erdogan repented for his murderous ways and sought absolution for his sins? Certainly not. The key is the forthcoming presidential and parliamentary elections in Turkey. They are scheduled to take place on June 18, but there is talk to move up that date for the convenience of the president.

Despite all appearances, Mr. Erdogan is not a statesman who shoots from the hip. His moves are calculated and far reaching. Thus far, he has been successful in spinning his web of international politics. During his rule, he has managed to shape Turkey’s political life in his own image and intends to further his control for another decade.

But the next election poses many challenges for him and for his country; the polls indicate that if the elections were held today, Mr. Erdogan would not win.

Erdogan wants to turn the year 2023 into a year of celebrations marking the centennial of the founding of the Republic of Turkey by Ataturk and anointing himself as his heir, or better yet, the second Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent. He has planned to inaugurate mega projects such as the second canal across the Dardanelles and an atomic power plant at Akkuyu and many other similar grand developments.