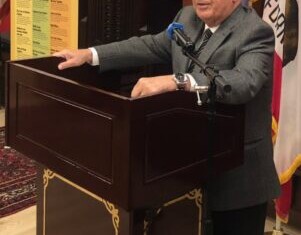

BOSTON — The Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston is among the top 20 largest art museums in the world and since this summer, it has a new director, Pierre Terjanian. A seasoned fundraiser, he was appointed Ann and Graham Gund Director and CEO after working at the museum as its chief of Curatorial Affairs and Conservation for about a year and a half. He is known as an important scholar on arms and armor, and previously worked curatorially at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Terjanian’s current position entails both administrative and leadership functions. He said recently: “I define leadership as dealing with the unknown when you don’t have a playbook and it’s not just management.”

His primary duties are to lead the institution and plan for it, while working with its board and overseeing all museum operations. This includes setting programs up for audiences and responsibility for the collecting work, exhibitions, and educational initiatives. “Ultimately,” he said, “it’s the job of bringing together the talent, energy and interest of the staff, the board, volunteers and partners in the entire community.”

Increasing Engagement

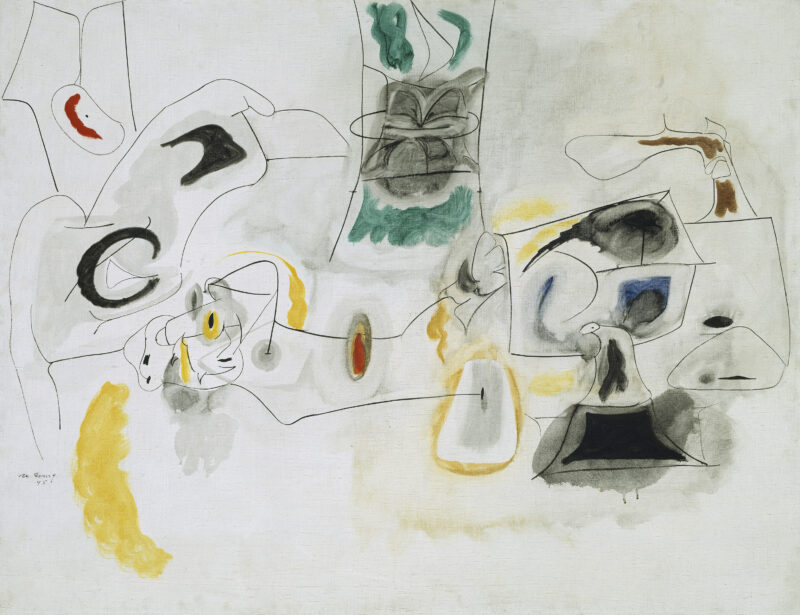

Terjanian observed that unlike audiences decades ago, ready to accept whatever narrative a museum proffered as authoritative, today people want to engage with art on their own terms, coming from their own interests. Most museums today therefore present their collections in a different way.

Terjanian has been thinking about refreshing the MFA’s approach to its permanent collection to generate a broader engagement with the arts. He wants to be able to appeal to both people who want to experience art as purely aesthetic and to those who want to get more of a learning experience out of art. Museums like the MFA are caught in between because they want art to be appreciated for its capacity to take us out of context, yet, he said, oftentimes, the art is a product of a particular context or experience.