By Lilit Shahverdyan

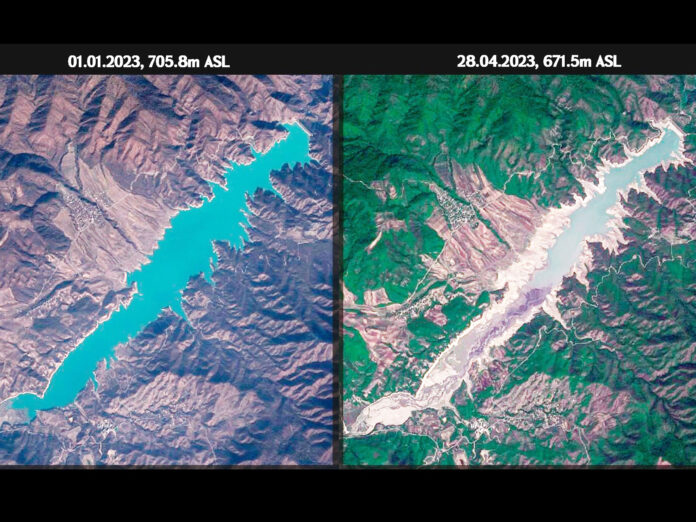

The Sarsang Reservoir in Armenian-administered Nagorno-Karabakh is reaching critically low levels. If it gets much lower, the region will face crisis-level electricity shortages and environmental catastrophe.

Karabakh has been largely dependent on the reservoir for electricity generation since early January, when cables from Armenia were damaged and could not be repaired amid Azerbaijan’s blockade.

The severe water shortage – sure to worsen as temperatures rise and precipitation reduces in summer – will likely make it impossible for Karabakh authorities to deliver on a deal to provide Sarsang water to nearby Azerbaijani-controlled areas for agricultural purposes. This raises the risk of “military provocation” from Baku, local officials fear.

Critical Levels Reached

Nagorno-Karabakh’s de facto state minister, Gurgen Nersisyan, reported on May 6 that in the first five months of 2023 almost three times as much water had been released from the Sarsang Reservoir compared to the same period last year. This while water inflow was half as much due to lower precipitation.