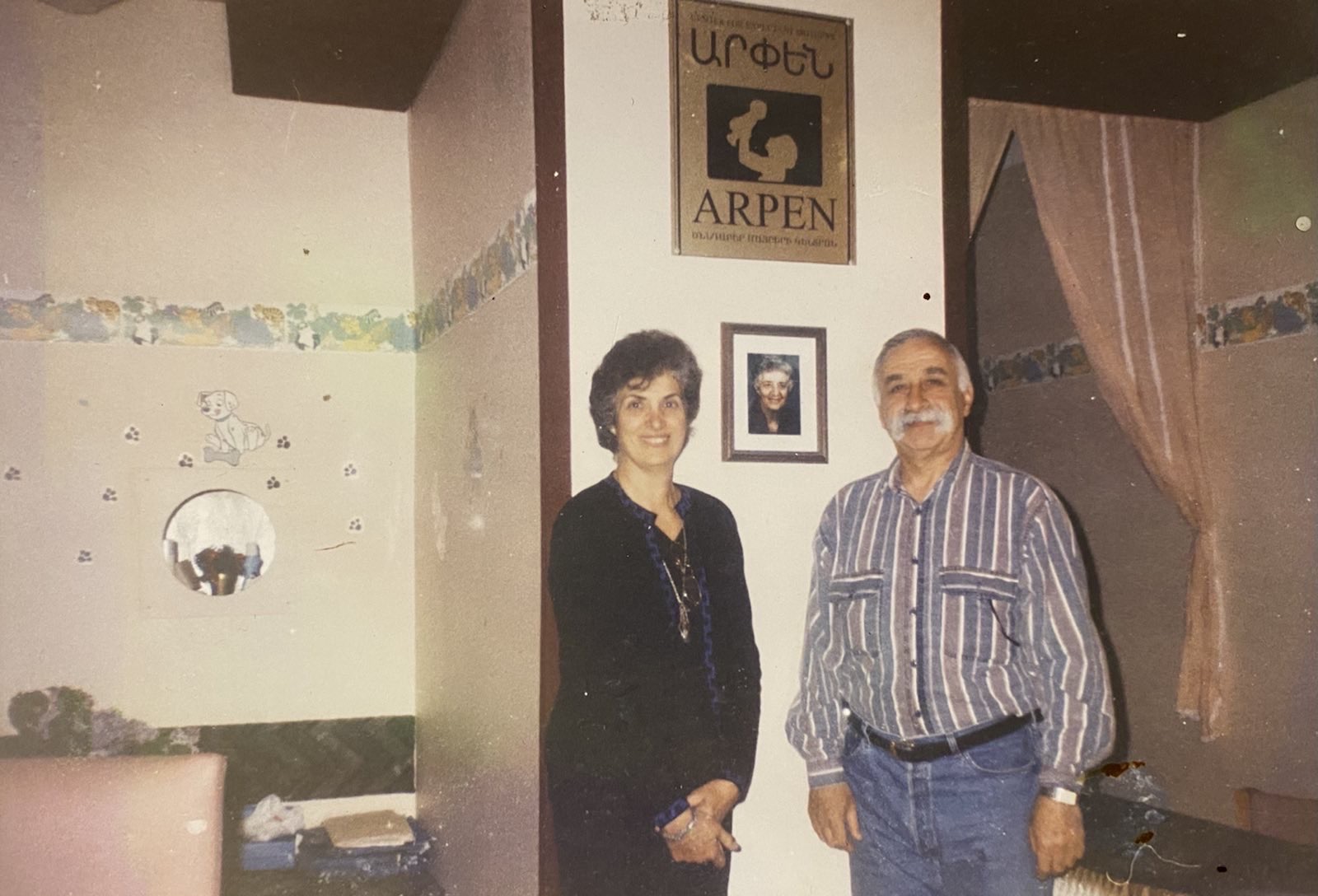

WATERTOWN — The Arpen Center for Expectant Mothers in Stepanakert has played an important role in maintaining demographic growth of the Armenian population of Artsakh for some 28 years. It was founded and supported by Dr. Carolann Najarian of Boston, with the aid of Prof. Gurgen Melikyan of Yerevan State University. It provided supplies necessary for pregnant women and assured their proper nutrition, and continues to do the latter to this day.

Melikyan declared, “The establishment of this center by Carolann Najarian and her husband George was one of the greatest patriotic acts possible. From December 1995 until the present, 33,026 children were born through that center. Can you imagine? 34,000 pregnant women have visited us, and this work continues today.”

In other words, the children born with the help of the center form a substantial portion of the 120,000 population of Artsakh today. Melikyan remarked, “I must say that the founders of the Center, Carolann and George Najarian, have greatly aided in the growth of the Artsakh population by lessening their economic cares.”

Tribute to Mother

Dr. Najarian, a graduate of the Boston University School of Medicine, began to travel regularly to Armenia after the terrible earthquake of 1988 to provide medical aid and supplies, and teach. Her assistance intensified during the first Artsakh War in the early 1990s. She related that she had been working with the Maternity Hospital in Stepanakert, capital of Artsakh, for some time in 1994 when the chief doctor there, Brina Marutyan, spoke about the fact that many young pregnant women needed help.

In June 1995, when Najarian’s mother passed away, she decided that in lieu of flowers she would ask for donations to found what became the Arpen Center. Arpen was the first name of her mother, who was born in Arapgir during or just before the Armenian Genocide. The center opened in December of that year.