WATERTOWN — Anush Aslibekyan is a multitalented woman, a prolific theater critic, short story writer and playwright who visited the US at the end of 2022 while her play “Mercedes and Zarouhi” appeared in New York. From 2008, Aslibekyan has been a researcher at the theater division of the Art Institute of the National Academy of Sciences of Armenia, and a lecturer on foreign theater and dramaturgy at the Yerevan State Institute of Theatre and Cinema from 2006, and completed her graduate aspirantura work in 2018. She has worked as a television reporter and commentator on Armenian stations and has been a cultural correspondent for the newspaper Azg for the last 5-6 years. In a wide-ranging discussion she revealed her views on art and Armenian intellectual and creative life.

Mercedes

“Mercedes and Zaruhi” was performed as a monologue in New York by actress Nora Armani, but Aslibekyan originally wrote it in the form of a short story based on true life episodes. She said that she heard the story of the heroine Mercedes from her husband’s mother, who heard it in turn from friends who had repatriated to Soviet Armenia. Aslibekyan said that she combined the stories of various Turkish-Armenian families to create a collective character typical for this period of time. She wrote the story with the shorter name “Mercedes” in 2012 and it was printed in the Nartsis monthly that year. It inspired great enthusiasm, Aslibekyan said, and she realized that the protagonists were suitable for drama, so she quickly turned it into a play in about five days, presenting the completed drama to several directors. Hakob Ghazanchyan, who in 2014 was both head of the Adolescent Spectator [Patani Handisates] Theater and chairman of Armenia’s Union of Theater Workers, telephoned to say that he saw the story of his grandparents in her play and wanted to direct it.

It was staged at the Adolescent Spectator Theater in the framework of events commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide. Ghazanchyan invited Armani from New York since she could speak both in Western and Eastern Armenian, which were used in the play. Armani performed several times and then left, with a young actress continuing in the role. The play was also invited to be performed at Cairo’s Experimental Theater Festival, and then for several days for the local Armenian community.

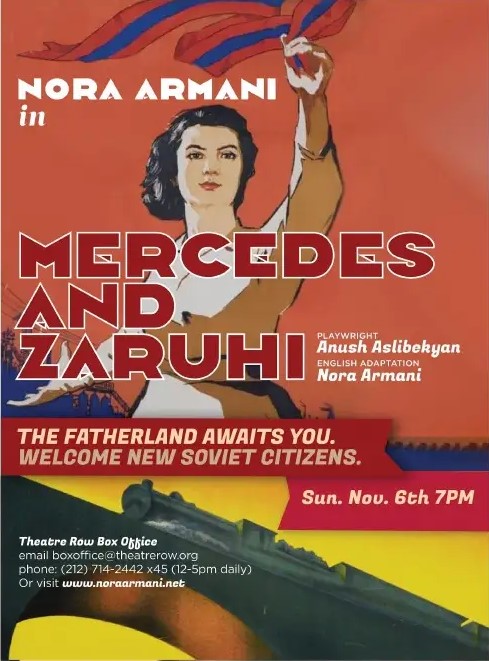

Later, Aslibekyan turned this version of the play, with multiple characters, into a monodrama and offered to place it at Armani’s disposal. The latter was invited to the United Solo Festival in New York, which is the world’s largest solo festival, and performed the new version of the play, which she translated into English, on November 6, 2022 in Aslibekyan’s presence.

Aslibekyan observed that the theme of repatriation to Soviet Armenia was not represented in Armenian dramaturgy and in general had been idealized, especially through propaganda in the Soviet period. Armenians returned believing that rivers flowed full of honey and milk in the homeland but immediately collided with a completely different reality, she said. “We are afraid to talk about this, but this is our history and we should not fear to confront history, because it is only by facing mistakes that they can be corrected,” Aslibekyan exclaimed. On the other hand, she said that when a historical topic turns into a theme for art, theater, film or literature, it becomes more popularized and those topics have their reverberations among the public, and she hoped that “Mercedes” had its distinct place in this process.