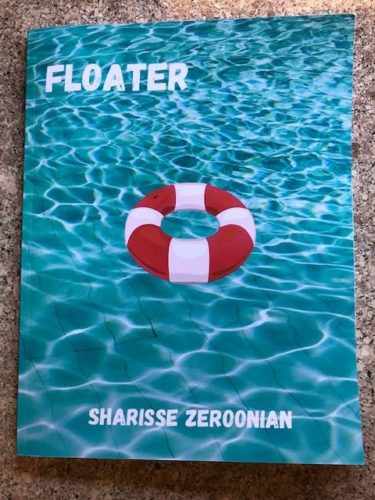

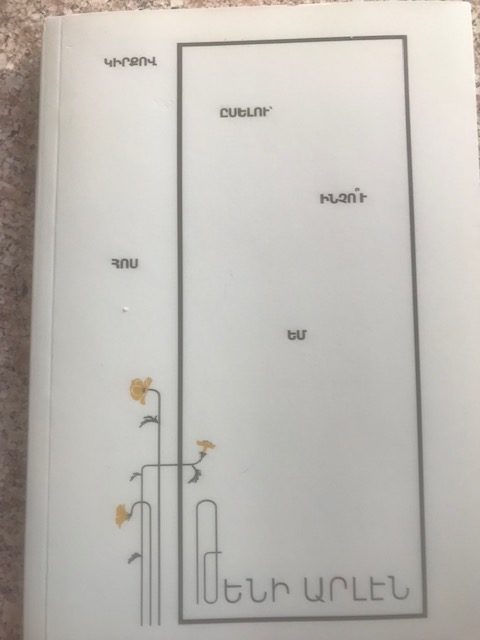

Published posthumously by the ARI Literature Foundation (Yerevan, 2021), with the support of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, the poems in To Say with Passion: Why Am I Here? show a depth of perception unusual for a 20-year-old. In these poems, Tenny Arlen mourns the loss of a child’s endless questioning, his endless “Whys.” Indeed, the persona in the poems trusts that if grown-ups did not, with their “I know”s, destroy a child’s sense of wonder and his curiosity, and instead “asked more questions, we would probably have no wars.” When man wants to be the center of it all there can be no holiness left in nature. “We set on fire, we saw, we empty,” writes Arlen. She, in fact, wonders if “climbing the silver staircase to the moon” would help answer life’s “inexplicable questions.” Even if life were to grant that possibility, however, it is a possibility Tenny Arlen was denied. The fledgling poet lost her life in a car crash a few months before starting the doctoral program in comparative literature she was admitted into at the University of Michigan—Ann Arbor.

Arlen’s questions posit a world full of fear, devastation, sadness, and especially loneliness. “I was born dead/voiceless,” confides the persona. Nonetheless, there is no outrage, no anger, in Arlen’s attempts to give expression to the devastation. No fear of the darkness either. Perhaps a degree of sadness that she is, “After all the promises and the waiting, alone in a an empty room,” that the “You and I” has changed to “I and I.” The pain is always confronted with courage and with awe. The questing artist is determined to create. “Words are within me,/they follow me,/they sing to me,/they talk to me,/I am not alone,” she insists.

While words do offer the persona some respite from the loneliness and the “vast silence,” “they can offer no solace.” Her older sister tells her of fairies that would whisper to her from under her pillows, but the younger sister never heard them “behind the trees and in the spiders’ cobwebs:” “I never saw them, not even one.” “Fairies are an illusion,” writes Arlen in “Memoirs,” a poem in the collection. We are ultimately alone.” “We die in silence.”

Arlen writes in Western Armenian, a language she started to learn in adulthood, but had no time to master. In fact, Arlen began her university education with no prior knowledge of Armenian and steered herself towards an Armenian identity. At 24, just a few months before she died, she changed her name to Soghovme. To Say with Passion: Why Am I Here? is the first full-length volume of creative literature written and published in Armenian by a US-born author.

As Dr. Hagop Kouloujian, Arlen’s Armenian language teacher at UCLA, also editor of the collection, avers, by putting the language to everyday use, Arlen helps keep Western Armenian alive and contemporary. When those who were born into Armenian and acquired it as they grew up — the best way to learn a language — abandon it, Arlen, who grew up removed from any Armenian community, goes out of her way to study it, and uses it to write poetry. The poet gives those who see no future for Western Armenian in the Diaspora much to ponder. Miracles do happen.