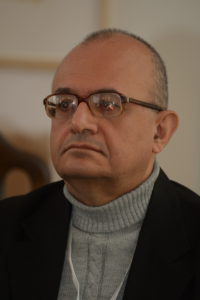

YEREVAN / CAIRO — Haig Avakian born in 1964, Cairo, is a musicologist, pianist, vocal coach, chorus master, publicist and philologist. He studied at Noubarian Armenian School, Heliopolis, Cairo; in 1983, he received a certificate from the Cairo State Conservatory’s piano department.

In 1988, he graduated from the piano and musicology departments of the Yerevan Komitas State Conservatory, then continued his post-graduate studies in 1988-1990. Since the age of 14 he has contributed to Egyptian Armenian and Arabic periodicals. As a concert pianist, he gave recitals and performed with orchestra in Cairo and Alexandria. He gave the first Egyptian performances of some works of Western composers and world premieres of Armenian and Egyptian composers’ works. In one of his recitals, he performed for the first time the complete solo piano works of the famous Egyptian composer Aziz Al-Shawan. From 1992 to 2001, he was the vocal coach at the Cairo Opera House. From 1992 to 2007, he worked as assistant and principal conductor for the Cairo Opera House Chorus. Between 2006 and 2010, he was the conductor and the artistic director of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina Chorus and the Bibliotheca Alexandrina Children’s Chorus.

Avakian edited, annotated and published 23 scores by Armenian composers (published by the Cairo AGBU branch), mostly based on original manuscripts. From 2001 to 2008 he published in Cairo the Dzidzernag musical quarterly (director: Mardiros Balayan), dedicated exclusively to Armenian music (29 issues). There he published music studies, and record, book and concert reviews. He translated into Armenian Egyptian researchers’ articles about Armenian music. Also published works by Armenian composers, as well as works by foreign musicians with Armenian themes. Since 2016, he has published series of supplements of Cairo-based Tchahagir weekly (48 volumes so far, most of them authored and compiled by him), that are available online.

Haig, I can talk to you about everything, considering your wide interests and well-awareness of the Armenian world and culture. Let’s start with music. What is the current state of classical music in Egypt?

In Egypt, classical music is not tied to traditional institutions. Undoubtedly, the Cairo Music Conservatory and the Musical Pedagogical Institution, as well as the Opera Theater, are important centers of education and culture. But their capacity in the area of 100 million people is quite limited. I am interested in the publication of classical Egyptian composers’ works. In 1997, I succeeded in preparing the critical edition of complete works of the first Egyptian classical composer Youssef Greiss (1899-1961) in 12 volumes with detailed notes in Arabic (available online). The manuscripts of famous Egyptian composer of Armenian descent Fouad al-Zaheri (Garabed Panossian) are under my hand, the publication of which (by Armenian funding) remains a dream.