YEREVAN — As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine enters its fourth week, its effects are being felt as far away as the Armenian capital. Across downtown Yerevan, a similar scene plays out almost daily as crowds of tall, Slavic-looking people — men, women, children, often entire families — conspicuously shuffle about, dragging carry-on luggage behind them as they look for their AirBnBs or hotels.

They are part of the more than 50,000 people estimated to have migrated to Armenia since hostilities began in Ukraine on February 24. The vast majority of new-commers are Russians escaping increasingly brutal political repressions back home as well as rumors of an impending martial law which could see many of them trapped inside Russia. However, smaller numbers of Ukrainians (believed to include those who had been stuck in Russia as well as ethnic-Armenian Ukrainian nationals repatriating) and Belarusians are also looking to make Armenia home.

IT professionals and other highly skilled people make up the bulk of this new wave of Russian émigrés, as entire Russian and international companies continue to relocate their operations to the Armenian capital to avoid the effects of Western sanctions. At least 140 companies relocated, or opened new offices in Armenia in the first two weeks of the war. 113 of these are from Russia, while smaller umbers of Ukrainian, Belarusian, Moldovan and Kazakhstani-registered firms made the move as well, motivated in part by Armenia’s ease of doing business which includes tax wavers for startups, and a particularly low turnover tax rate among many other benefits.

“Our company sent us a message on Saturday morning announcing that they chartered a bus to Demededevo [Moscow’s International airport] later that same day to relocate us to Yerevan,” said Sasha, an IT worker from a city in central Russia. Sasha, whose last name and place of work were withheld for security reasons, says he packed up what he could carry, took his family and flew to Yerevan where his company also maintains offices. “We knew the Caucasus had a tradition for hospitality, but I was surprised by how warmly we were welcomed,” he added.

For many escaping Russians, however, Yerevan was simply one of few remaining options as tit-for-tat overflight bans between Moscow and Brussels closed up most European destinations. “We chose Armenia because it’s close enough and remains one of few places in Europe that isn’t hostile to Russians,” Igor, another newly-arrived Russian, told the Mirror-Spectator. Armenia’s pro-business regulations also make it easy to work out of. Igor noted he was able to find an affordable apartment and open a bank account and is now waiting for his wife and children to join him in Yerevan.

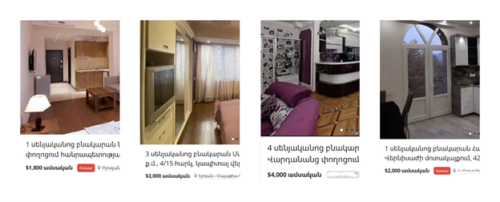

Renters Beware