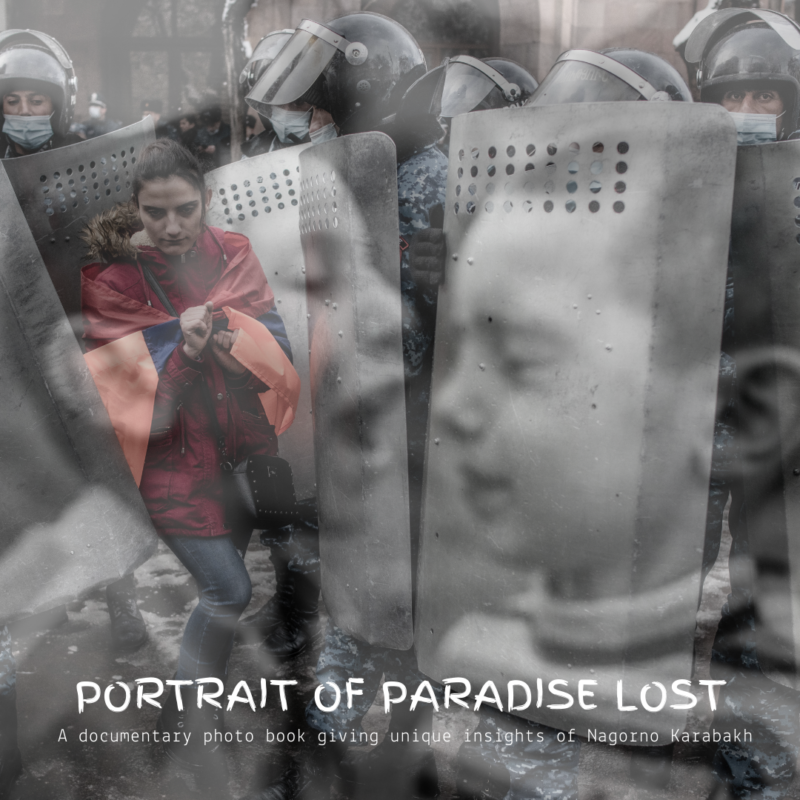

WATERTOWN — Israeli photojournalist and documentary filmmaker Gilad Sade began visiting Artsakh in 2015, quickly establishing strong friendships with many of its inhabitants living in some of its most remote villages. He was present during various episodes of the 2020 war and its aftermath and is preparing a book which will include photographs from that time as well as of people and places that may no longer exist in the same way after the war. He calls the book project “Portrait of Paradise Lost.”

Sade began to describe his work with the words, “I think Artsakh was for me one of the hardest projects I did, both in the long term but also during the war.” Sade grew up in the West Bank, in the midst of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and became a member of the extremist Hilltop Youth Movement. He eventually devoted himself to peace and traveled to many different conflict zones to raise awareness of human rights issues. He issued his first book of travel photos in 2021, Travel Warning Photobook, in a limited edition of 100.

In the summer of 2015, Sade was working as a mountain tour guide in the Republic of Georgia and decided to go next to Armenia with the goal of visiting Karabakh for the first time. He said, “I was a bit anxious and not sure how it would be. I imagined basically that I am going to a place where everyone is in the street with Kalashnikovs and camouflage. This was the kind of information that was available on the Internet about Nagorno Karabakh. But I made a friend in Yerevan, and this girl, she was telling me, you know, ‘I am from Artsakh.’ She started to share information with me – how nice, how welcoming, how beautiful the place is.”

He went with her in her tiny car, he said, to Kelbajar/Karvajar and arrived at the border where there was a checkpoint and a little cabin. He wondered where all the militants were that he was curious about. The men at the checkpoint were curious about him too and invited him to drink vodka and eat food. He said, “We drank I don’t know how many genats’s [toasts] and ate food, and I was at the border and was almost dead drunk already. That was my welcome.”

One month and a half later, he came again for twelve days, and again returned at the end of 2016 to spend New Year and Christmas in a village in Hadrut with new friends. Sade said, “Ever since, I went there really often – so many times. I would come whenever I had free time.” He had one main goal. He said, “I wanted to understand the conflict. I wanted to understand this place because I saw what is in the media and what is the reality, and I wanted to dive into that. By diving into that, I mean I really went to every place possible. I went with people who took me to Aghdam and other cities. I wanted to see and understand what the conflict is, what is the situation, and how people live.”

He said that because he also grew up in a conflict zone, he understood that the status quo could not continue there. Sade declared, “In a way, I predicted that there will be a war, but I didn’t predict that it would be so early.” Thinking in that way, he decided, “I will go here. I will document the life of the people. I met people in the villages who became my very, very close friends. It was just amazing for me. But also I realized that my footage might be the only footage of some places. If there would be a war, these places might never exist again. I committed to the story of Artsakh.”