LOS ANGELES — For more than 50 years, Sona Karakhanyan couldn’t remember anything about her own life as an exile in Siberia. She thinks that it was a trick that her brain played in order to protect her from the horror of the past. When her father, Abraham Karakhanyan was speaking about his experience, his recollections of her family’s life, she would listen and memorize them: but, somehow, these memories weren’t hers.

In 2007 Sona was watching a television show where a woman was familiarly wrapped in a shawl made of wool. That scene instantly took her back to her childhood when she was 4 or 5 years old, didn’t have warm clothes and her grandmother would wrap her in a similar shawl while taking her outside to the village inhabited by exiled families in the blue frost of Siberia.

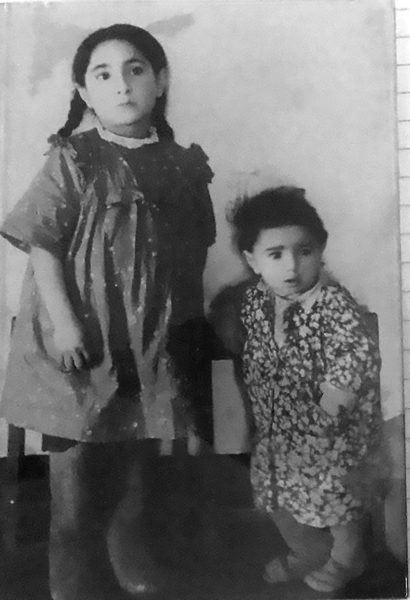

She said, “I remembered everything, the house, people, their faces…I remember how they would give me raspberries gathered in the woods and placed in a folded paper bowl. I remember my cousin, who was in exile with us. Those were unpleasant memories. How can you remember that you didn’t have a shoe?”

Sona pauses for a second. I can see her eyes filling with tears and drifting far away from Los Angeles, from me, from our conversation. Then she is back. She remembers her grandmother who would squeeze her grandchildren to her chest and tell them tales from her past life filled with glory, and ardor, hope for salvation and better days ahead.

Abraham Karakhanyan was the son of Fr. Hovsep Karakhanyan, the priest at the Saint Gevorg Church in Charmahal province in Iran. He used to be a senior supervisor in the Armenian schools of Charmahal and also held a higher position at the English oil company IPEOC in the south of Iran. When the second wave of the big Repatriation started in 1946, Fr. Hovsep was in Bombay as a missionary, and Abraham decided to join thousands of Armenians in Iran who were granted the opportunity to build a new life in the homeland.

The Karakhanyan family — Abraham with his mother, wife, two daughters, son and a nephew — moved to Sisian, Armenia.