WYNNEWOOD, Penn. — “A nation that forgets its past has no future.” This quote, often attributed to Sir Winston Churchill, serves as the inspiration and guiding force for a group of hard-working volunteers who are giving of themselves to preserve the past.

The Archives Committee of St. Sahag and St. Mesrob Armenian Apostolic Church, located in Wynnewood, outside Philadelphia, has been working to collect and organize documents, images, and artifacts from the church’s history. The church has a long history to preserve, with its name dating to the very first sanctuary purchased by the city’s Armenians in 1913. As the community grew, St. Sahag and St. Mesrob Armenian Apostolic Church was officially chartered in 1924 to serve the city’s western region and has moved multiple times before settling at its Wynnewood home in 1963.

Being such an old parish, its archives encompass the early generations of Armenian immigration to America. Even its setting is historic, as the church occupies the 1885-built Ballytore Castle, one of the iconic mansions of Philadelphia’s famed “Main Line.” Over the decades, the mansion’s tower had become a repository for all manner of the church’s papers and items. Curious about what it might hold, one summer day in 2015 Alma Alabilikian and Linda Babikian took a peek inside with the notion of organizing it into an archive. What they found was a room stacked floor to ceiling full of containers. Donning rubber gloves, they undertook the herculean task of sorting everything over the next five weeks, salvaging what they could from time-damaged materials.

Very Rev. Fr. Oshagan Gulgulian, pastor, suggested using the tower space as an archive, and by the next spring a committee of volunteers was formed. Alabilikian’s enthusiasm for the project led her to consult archivists from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Arcadia University and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and she took on the role of committee chair. Babikian adapted the suggested archival procedures to create a database for incoming documents and information. They were joined by librarian Pauline Babikian; the committee’s historian, Elizabeth Barsamian, with her decades of service to the church and encyclopedic knowledge of who’s who; and Sonia Garabedian, who serves as liaison to outside organizations. Haig Geovjian and Peter Paone joined as advisors. An oral history component was also created to record interviews with church elders in order to preserve first-hand accounts of the church’s history, made up of interviewer Steven Barsamian, producer Raffi Berberian, and coordinator Carol Keosayan. Unfortunately the Covid pandemic prevented much progress in the latter endeavor.

The committee was able to intercept a cache of artifacts in the basement heading to the dumpster. Within it they were surprised to find documentation that some parishioners had put up their homes and businesses as collateral to secure a mortgage for the purchase of the current church property. This formerly lost piece of history really encapsulated the drive behind their mission, as Alabilikian described: “We have found it remarkable in reading all of the Parish Assembly Reports and Banquet Booklets – records of events going back to the establishment of the parish, all the time, dedication, effort, and the money that have been expended to keep this church, its Armenian identity and Christianity alive. It’s easy seeing the church today to take for granted how much effort and struggle went into making it a reality, especially considering how many of those people were Genocide survivors escaping persecution, coming here without knowing the language and with no aid to get established.” Babikian agreed: “Growing up, most of us knew these people, unaware of all they did to form the vibrant parish we have today. Their faith really resonates in our research, [and is] reflected in the risks taken to keep their people together.”

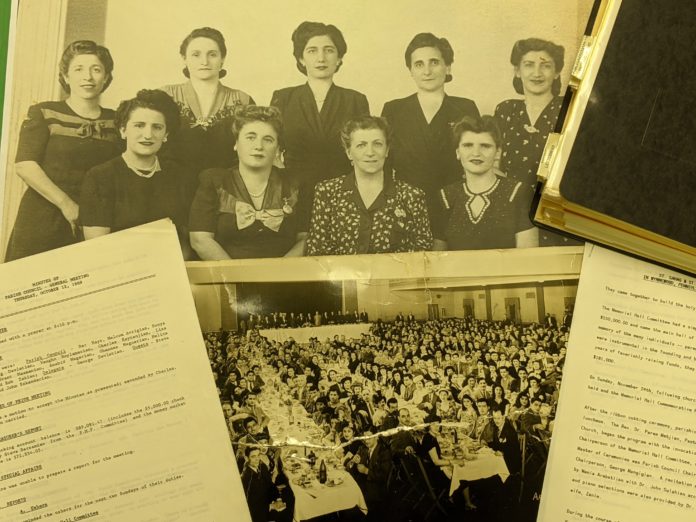

It’s always a joy for the members to make discoveries and learn new things from these materials. Some of their favorite finds include a 1928 banquet photo, where many of the attendees were Genocide survivors looking prosperous and well; beautifully handwritten minutes of the Ladies Aid Society and Women’s Guild; and a compilation of church newsletters since 1960. Realizing that many of the photographs needed identification, the Archives Committee enlarged them to poster size for display at church functions hoping that parishioners could identify them. One photo was a silver gel studio photo of the Ladies Aid Society members. The group was stunned when one young man looked at it and said, “This is the best picture I have ever seen of my grandmother!” Another is of an Armenian-American veterans banquet to celebrate the end of World War II, in which the young returned vets are seated alongside the survivor generation who gave their children to defend their adopted homeland.