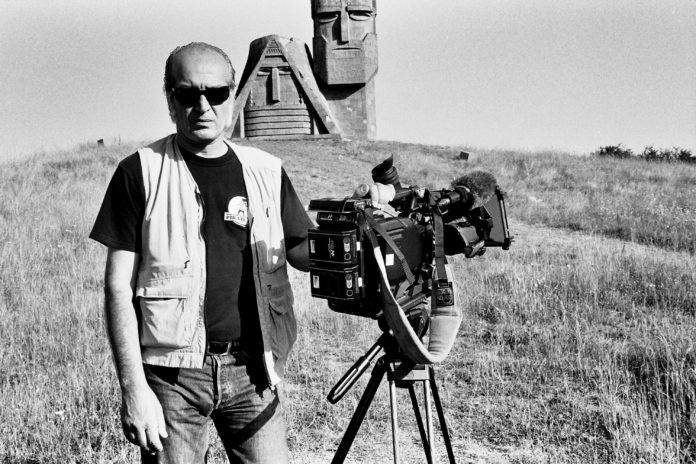

YEREVAN / VILLEBON SUR YVETTE, France — French documentary filmmaker, writer and cinematographer Frédéric Tonolli (born 1959) spent most of his childhood in Villebon sur Yvette, where he still resides. He has filmed and directed numerous documentaries for French public television channels. In 2009 he directed for France 5 a series of documentaries of four episodes retracing nearly a century of geopolitics around oil, from Norway to Iraq. From 2011 to 2014, he directed a new series of four documentaries on love stories in cities at war (“Sarajevo, my Love,” “Berlin, my Love,” “Baghdad, my Love” and “Belfast, my Love”). His filmography includes also “Blood of the Mountains” (1994), “The Lords of Behring” (co-director: Patrick Boitet, 1995), “Profession Profiler, Micky and the Black Wind” (1999), “The Nine Moons of Behring” (2003), “The Powder Box of Caucasus: My Little Papers from Armenia” (2005), “People of Water” (2006), “Upside down, the Arctic” (2008), “Children of the Whale” (2008), “The Death of a People” (2009), “The Secret of the seven Sisters” (documentary series of four 52-minute episodes, 2009), “Baghdad Taxi” (2012), “Syria, the Children of Freedom” (2013), “Normandie-Niemen” (2014), “The Forger of Vermeer” (2017), “Guyana: the Gardeners of Exile” (2018), “Trapped: The Bataclan” (2020), etc.

Frédéric, I have an impression that for you the whole planet is a big family and you easily access the homes of all family members. Am I right?

Difficult to answer if the world is one big family. I cannot say that I feel good everywhere, it can happen that the environment is hostile and does not want you. So I try to manage to get invited or to be invited. I do not come as a conqueror. I am not at home, but I like that they make me feel at home. That is different.

You have worked in many countries, including Madagascar, Ethiopia, South Africa, Yemen, India, Indonesia, Equator, Guyana, Armenia, etc. What was your most memorable adventure?

It is impossible to answer. It would even be a lie or a distortion of the truth. Every journey, every film is an extraordinary adventure. I am not a tourist. I have the chance to live my life working. My work is my life, my life is my work and it all blends together. I often say that I am lucky to earn my living by living, even if sometimes I earn it very badly, in the pecuniary sense (laughing). All my adventures have been great because they were my adventures. Otherwise to try to answer your question: the years I lived among the Chukchi in the Behring Strait are unforgettable and all the stays I made in the early ’90s in the Martakert region of Artsakh with Vladimir’s Squad remain engraved in my heart and I think about them almost every day. But I do not live in the past, I just keep it with me forever, like suitcases that accompany me all the time.

Although your experience on those countries has been reflected in your films, have you considered writing a book on your travels?