By Joseph P. Kahn

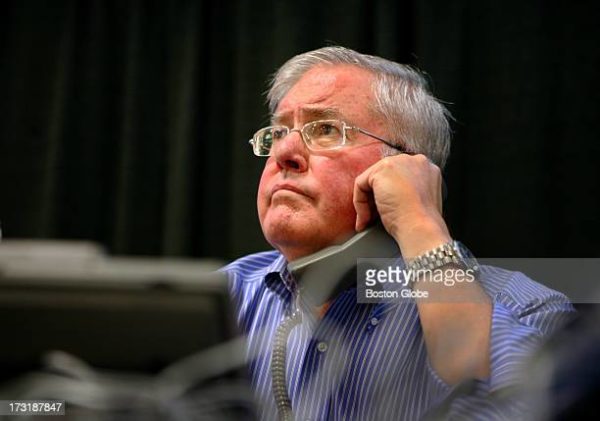

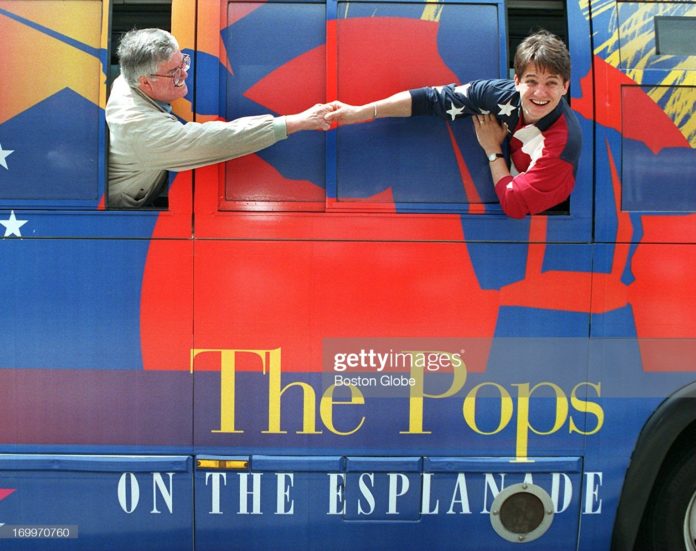

BOSTON (Boston Globe) — David Mugar, a prominent businessman and deep-pocketed philanthropist who injected ’ fireworks and cannon fire into Boston’s annual Fourth of July celebration, one of many contributions to civic life that left a lasting imprint on the city and region, died Tuesday, January 25. He was 82.

As chairman and CEO of Mugar Enterprises Inc., Mugar oversaw a sprawling, privately held empire comprising real estate holdings, retail businesses, performance venues, and other investment- and arts-oriented enterprises.

Beginning in 1982, he served as principal owner of WNEV-TV (Channel 7, now WHDH- TV), then the local CBS network affiliate, for more than a decade. As executive producer of the July Fourth Esplanade show, he almost single-handedly transformed the event from a parochial celebration into a star-spangled extravaganza seen by millions on national television.

A scion of an Armenian-American family that built the Star Market grocery chain, Mugar belonged to an elite group of donors whose wealth and influence reached into virtually all aspects of public life, from college libraries and concert halls to hospitals and shopping malls.

In Greater Boston alone, the Mugar family name is affixed to the Museum of Science’s Omni Mugar Theater, Boston University’s Mugar Memorial Library, Northeastern University’s Mugar Life Sciences Building and Mugar Hall at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Diplomacy.