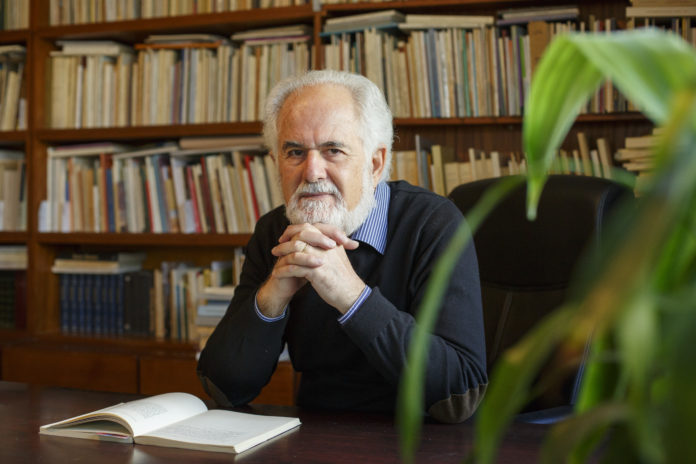

YEREVAN / NICOSIA — Cypriot writer and translator Giorgos Moleskis was born in 1946 in Lysi, Cyprus. He studied at the Nicosia English College and at the Lomonosov Moscow State University. He has an M.A. in Russian language and literature and a Ph.D. in literature.

He worked at the Cultural Services Department of the Ministry of Education and Culture of Cyprus, as Senior Cultural Officer and was the Executive Adviser of the Cyprus Symphony Orchestra Foundation. He was president of the Committee for State Prizes for Literature, the Cyprus National Jury for the European Prize for Literature and the Union of Cyprus Writers.

Moleskis received an Honorary Diploma and Prize for Poetry from the Cyprus government, as well as the Pushkin Medal from the Union of Russian Writers. He is, also, an Honorary Member of the State Academy of Slavic Culture of the Russian Federation, the Union of Cyprus Writers and the Greece — Cyprus Cultural Association.

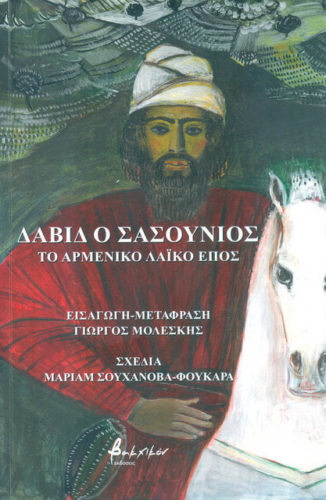

Since 1967 he has published thirteen poetry collections, two books with collected poems and five books with poetry translations. Some of his books are: Vladimir Mayakovski (introduction-translation-comments, 1995), Russian poets of the 20th century, an anthology (introduction-translation-comments, 2004), Awaiting rain (poems, 2008), Contemporary Turkish Cypriot Poets: An attempt to communicate (introduction-translation, 2010), The unfinished poem (2014), When the sun enters the room (short stories, 2017), Russian poetry 20th century, (introduction-translation-comments, 2019), Every July I return (2019), Vladimir Mayakovski, Pre-Revolution Poems (introduction-translation, 2019), David of Sassoon, The Armenian Folk Epic (2021).

Nine of Moleskis’ books of poetry books were translated and published in separate volumes in France, Italy, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria and Albania. His poems have been translated and published in literary magazines and anthologies in Russia, Germany, France, Italy, Bulgaria, Rumania Turkey, Ukraine, Finland, Armenia, Estonia, Spain, Chile and other countries.

Moleskis lives in Nicosia with his Armenian wife, they have three children.