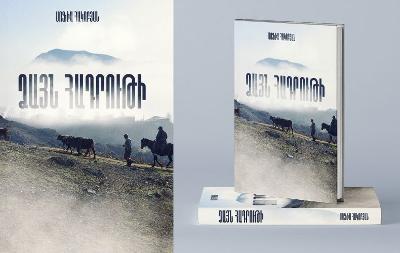

YEREVAN — The new book by Turkologist and journalist Sofia Hakobyan, titled Dzayn Hadruti [The Voice of Hadrut], was published by the Gevorg Virats Publishing House recently. It comprises the memories and experiences of the Armenians of the Hadrut region, which was occupied and emptied of Armenians as a result of the terroristic attacks of the Turkish-Azerbaijani lineup in the last war of 2020. The book is published in three languages.

Hakobyan explained why she wrote this book: “As a Turkologist and journalist, for nearly 10 years I have studied the Islamized and Christian Armenians living in Turkey. I thought that there is practically no one speaking on this, whereas it appears that probably Artsakh does not yet need me. However, of course 2020 turned the course of everyone’s life around. In October of last year, when our compatriots displaced from Hadrut appeared in Armenia, I periodically heard from them about the killings of the peaceful inhabitants of this or that village and those who went missing. It was clear that we were dealing at that very moment with ethnic cleansing, and it was clear that we did not realize how important it was to record those stories at that very moment.”

A particular incident was the final spark. She said, “I remember that during those same days the president of Azerbaijan in an interview given to one of the foreign media assured that the people of Artsakh were ‘their citizens’ and that they were ready to provide them with the best living conditions. The director of Mediamax.am, Ara Tadevosyan, very aptly countered that interview of Aliyev by offering him [the opportunity] to give an interview to the Armenian media and state what were those ‘best’ living conditions that awaited the people of Artsakh within Azerbaijan. Of course, they did not respond from Azerbaijan, but at that very moment, as they say, that ‘lamp’ lit up and I proposed to Ara Tadevosyan to show that ‘best life’ which the Azerbaijanis brought to Hadrut.”

According to Hakobyan, the people of Hadrut convey their own messages through this book. She said, “The purpose was to create that very platform, to try to give the Hadrut people the right to that voice of which they are deprived by the country whose armed forces now control Hadrut. The problem is that when discussing wars, people talk about territories but do not talk about the people living in those territories. Within the framework of the project, we conducted more than twenty interviews with forcibly displaced Artsakh residents from various villages of Hadrut. We tried to include representatives of various groups of people, such as women, men, the elderly and youth, medical workers, returnees from captivity, and relatives of peaceful residents who were killed.”

She said that the interviews appear without interventions or interpretations, though information about the history and culture of particular villages mentioned are given at the end of interviews. The interviewees are unarmed peaceful inhabitants who should not have been perceived as legitimate targets of Azerbaijani actions during the war, with even the men not of the age of military conscription.