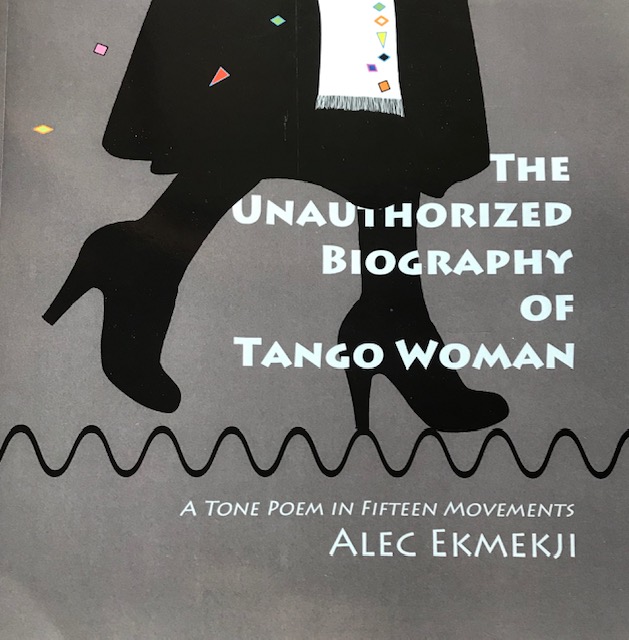

Alec Ekmekji’s The Unauthorized Biography of Tango Woman: A Tone Poem in Fifteen Movements is an eloquent reminder of the redeeming power of beauty. The recently published volume of haikus and illustrations, (August 2021), confirms French writer Alain Robbe-Grillet’s words, quoted in the book, that “The true writer has nothing to say. What counts is the way he says it.” Indeed, Ekmekji’s book testifies to the power of words, and of images, to help transcend the trauma of a past, no matter how destructive or how painful that past has been.

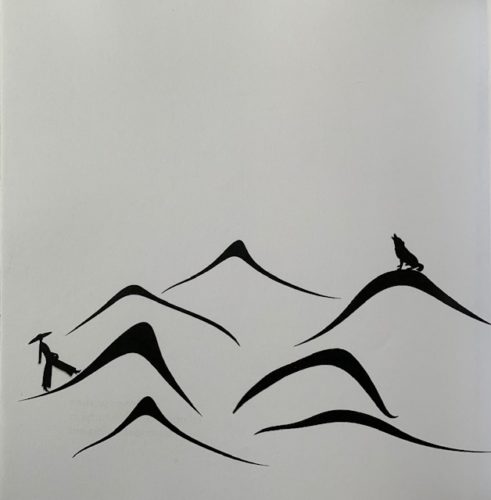

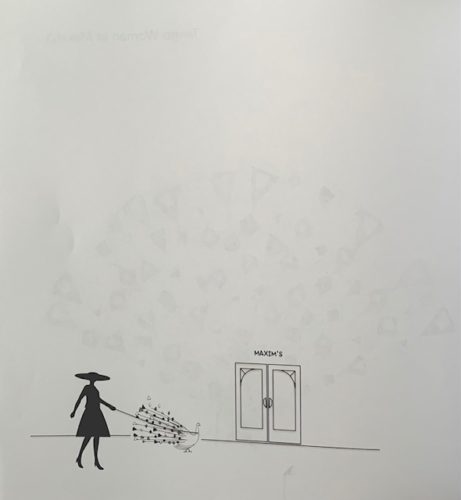

The Tango woman’s biography may be “unauthorized,” yet it has the authority of lived experience behind it. The woman who “writes long haikus in the sand” and who “does yoga with the swallows,” moves around in the company of history’s greatest. Einstein holds the elevator door for her. Proust hears every word she confesses at La Madeleine. Socrates, Mozart, Beethoven, Strauss, Chopin, Rodin, Kafka, Truffaut are all inspired by her. There is nothing gossipy about the flattering portrait of a woman who is cherished and admired by all.

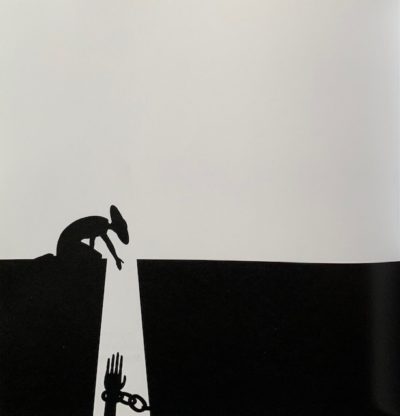

Nonetheless, Tango woman longs for her roots. She confronts a present of exile with memories of her rich Armenian past. The poems invoke Ara Keghetsig, an Armenian king renowned for his physical beauty. They invoke King Ardavazt, the first Armenian playwright of classical Armenian theatre, and also Dikranagerd, the ancient Armenian capital of King Dikran the Great. But they also recall the horrors of the killings and the deportations that forcibly removed her people from their ancestral lands and scattered them into the remotest corners of the world. “My tango woman/sings me The Song of the Bread/does Varoujan hear?” evokes the silencing of an entire generation of our poets at the onset of the 1915 Genocide. An all-black page—the only all-black page in the book—accompanies the seventeen syllables that conjure this darkest chapter in our history.

No matter how chilling the memory, however, the reader’s attention is inevitably called to the words and to the images that dramatically capture the spirit of the poems. “My tango woman/hands a pistol to Tehlirian/Gomidas forlorn” shocks and upsets, but it also captivates with Ekmekji’s astonishing ability to compress so much history into a few syllables.