LONDON — George Jerjian calls himself a “mindset mentor,” and writes self-help books for baby boomers about how to find purpose and passion in their retirement. He practices what he preaches. Jerjian has made it one of his own passion projects to bequeath to the Armenian community, the academy, and the world a priceless set of photographs which his grandfather took in pre-Genocide Western Armenia.

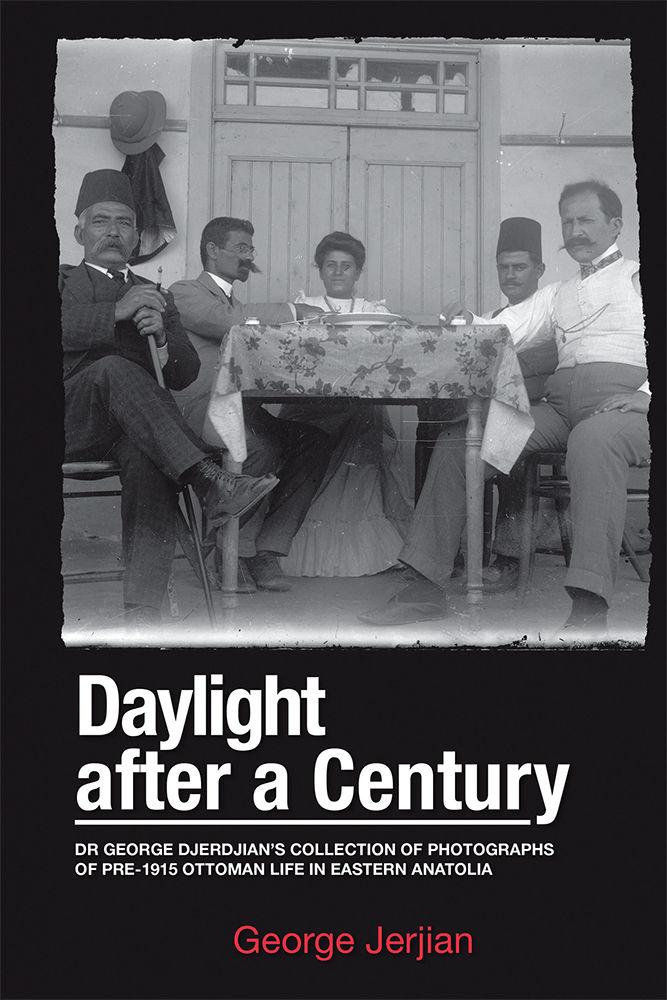

Jerjian was the featured speaker in an August 21 webinar where his documentary “Daylight After a Century: Dr. George Djerdjian’s Collection of Photographs of Pre-1915 Ottoman Life” was screened, followed by discussion. The webinar was hosted by the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR), the Ararat-Eskijian Museum, the Armenian Institute (London), and Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archives.

Marc Mamigonian, the director of academic affairs at NAASR, introduced the speaker and representatives from the sponsoring organizations. The discussants stressed the vast importance of saving archival materials, and issued a call to the Armenian community, that anyone with written or printed documents, photographs, and artifacts, which shed light on Armenian life and history, must preserve these at all costs. Jerjian went further, calling on Armenians to “not be selfish” and to share their what has been passed down to them with the broader community, as he has done.

The documentary, which was made in 2014 along with a companion book (both titled “Daylight After A Century”), depicts the restoration of approximately 100 photographs taken by Jerjian’s grandfather, Dr. George Djerdjian of Arabkir. Djerdjian attended the Sanasarian Academy in Erzurum and medical school in Zurich, settling in Egypt and later in the Sudan. The photographs were taken between 1900 and 1907, on an old style camera that used glass plates. These glass plates have been preserved by the Jerjian family for approximately 100 years before being brought out of storage by the younger George Jerjian and developed by the specialty firm Chicago Albumen Works in Housatonic, Mass. (The speaker, George Jerjian, spells his name without the “d” of his ancestors.)

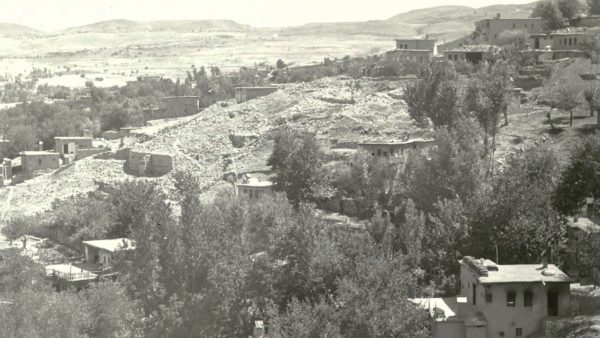

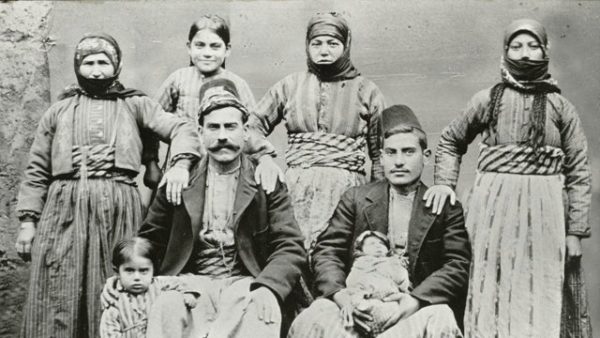

The photographs depict an astonishing array of figures and locations in Ottoman Armenia, predominantly in Arabkir and Erzurum and locations in between the two where Djerdjian travelled. Djerdjian had an eye for the interesting; the photos include everything from waterfalls, rivers and mountainous landscapes to town street scenes and Armenian folk musicians; to Armenian churches and schools; to an ominous gathering of Ottoman officials on the eve of the 1908 Revolution. The documentary depicts the story of the slides as well as Jerjian commenting on several of them; the post-viewing discussion found Jerjian quickly going through a larger number of slides and giving more interesting commentary.

The documentary also had commentary from Dr. Rouben Adalian, the executive director of the Armenian National Institute, who expressed the great importance of Jerjian’s find, and its value to Armenian history and Armenian studies. The emphasis Adalian places on this collection of 100 photos is telling. A similar discovery in an American or European context would not have the same effect — 100 photos of buildings in London that were subsequently destroyed in the Nazi blitz, for example, would certainly not excite the same amount of curiosity. The fact that such a collection does so in an Armenian context is testament to the destruction wrought during the Genocide of 1915; that such photos are rare and that so many pieces of the puzzle are missing from Armenian life before the Genocide — even to the grandchildren of those who lived in that world — is a sobering reminder of how much has been lost and how vital it is to preserve what is left, as the discussants encouraged.