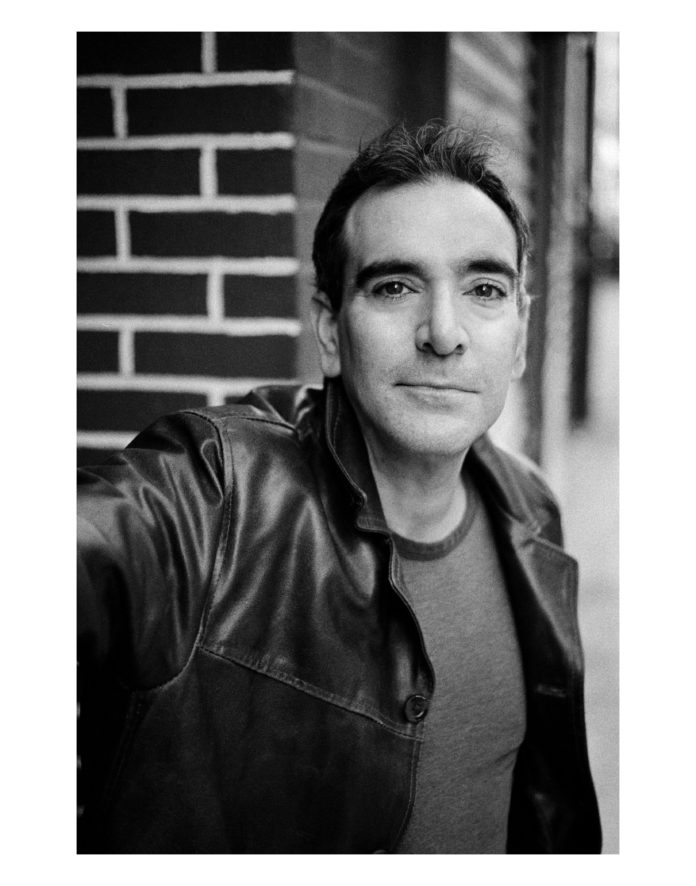

Aaron Poochigian’s fourth book of poetry, American Divine, confirms him as one of our important poets, with both a formal mastery of his craft and important things to say about the human condition in 21st century America. While he was brought up in Grand Forks where his father Donald taught Philosophy at the University of North Dakota, Poochigian’s Armenian roots go back to the town of Peri in Western Armenia via Fresno, home to other well-known Armenian writers such as William Saroyan, Charlie Minassian and Aris Janigian. Poochigian earned a doctorate in classics and is also a prolific translator. On the occasion this year of the bicentennial of French poet Charles Baudelaire’s birth, he is coming out with a new translation of The Flowers of Evil on Norton Press. It’s the author’s eleventh book, which says something about his creativity and work ethic.

Geography plays a pivotal role in American Divine. It sets the stage for a look inward at Poochigian’s faith in both God and man — his relative lack of faith as well as his search for it, in what I sometimes call The Big American Empty. Poochigian moved to New York in 2011; the Midwest’s loss has been our great gain. Here in “American Divine” the poet pens a love letter to his adoptive city, but also in a sense to the other America which he left behind, a place which he prefers to forget yet cannot quite ever leave behind. The book is divided into three sections: “The One True Religion,” “The Uglies” and “The Living Will.” It’s no accident that Section Two of the book bears the title “The Uglies.” In his seminal “Welcome Home,” the poet describes North Dakota in less than flattering terms, telling the reader outright: “I’ve got no patience for Dakota Zen,” before intoning:

I grew to hate the place — a vast ho-hum.

Thing is: I fought against it with such force

So goddamn long that I got owned, of course

and now it’s always where I’m coming from.