To you liberals, of course, goats are just sheep from broken homes.

– Malcolm Bradbury

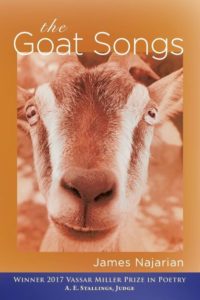

Winner of the 2017 Vassar Miller Prize in Poetry, James Najarian’s The Goat Songs is many things: an American pastoral to Berks County, Pennsylvania where he grew up, an ode to the male body, as well a paean to all things caprine. It is also one of the most promising and cleanly written books of poetry to have been published of late. The author’s precise language and his rich vocabulary should surprise no one perhaps, coming from a Boston College English professor who specializes in Keats. The range of topics, as well as the intimate portrait of a family history that stretches from ancient Armenia to modern-day Pennsylvania is told with psychological accuracy and verve: the result is a wonderfully idiosyncratic tome that is bound to surprise.

Najarian divides the book’s first section, “Armenia, PA” somewhat equally between old and new. Though a graduate of Lawrenceville and Yale, Najarian grew up on a farm and makes the reader privy to things both pedestrian and arcane about goats. On their naming: “There’s Bippy we cry out, “There’s Charmian.”/In general they had attractive names/that you would hesitate to give your daughters:/Candy, Ceffie/Bambi, Serenade–or sometimes a descriptive sobriquet:…Regina for a royal Roman nose; /Frisbee for one who leapt all fences…” In “First Kidding” the poet recounts in some detail how a kid goat is born. And finally in “The Goat Song” (again) we find out “But goats live only six or seven years./In our herd, they seemed to die unceasingly/like heroines from nineteenth century opera — of mysterious, long-thought curable diseases.” The goats smell of “The shit-and-lemon cologne they carried on them” and we learn “How they hated/two things above all: being alone, and rain.”

In “Near Apex PA” Najarian cleverly mixes topography with human geography when describing the surrounding mountains: “The Kittatiny, the Running Mountain/ divides this country with its slack axe,/lopping the hemlock from the oak,/Slav from German, farm from quarry.” Elsewhere in “Taking the Train from Kempton PA,” he addresses the viewer in the imperative mode, advising him to “…roam unregarded behind back yards./So skirt a black wall,/follow the shallow creek, and head for the woods–.” Later in the poem he again delicately mixes what is natural and manmade — I headed for my google to find out what the vegetation he describes actually looks like: “Mayapples crowd the edge/where you should be./In that dull rumble/only a tractor on the new highway?…Wet jewelweed sifts through the ladder of track,/and ahead, in light,/a shed peeks out from its habit of burdock:”

From Pennsylvania the poet takes us to pre-Genocide Armenia in “Armenian Lesson,” an ode to the Armenian alphabet where each quatrain ends with a refrain from Gulian’s celebrated Armenian Grammar of 1904. After describing the language’s gutturals and other peculiarities he ends the poem: “We are expecting too much from this tongue–/more than thirty-eight letters can give,/No living language could ever be strong/enough for those it could not save./The Turkish soldiers are very brave.” Indeed, perhaps we are…