By Razmig Bedirian

PARIS (TheNationalNews.com) — When Kegham Djeghalian stumbled upon three red boxes tucked away and forgotten in his father’s wardrobe in Cairo three years ago, he couldn’t believe his luck.

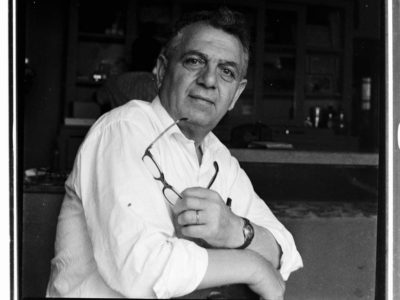

The boxes contained the negatives of more than 1,000 photographs taken between the 1940s and the 1970s by Djeghalian’s grandfather, also named Kegham, who founded Gaza’s first photography studio.

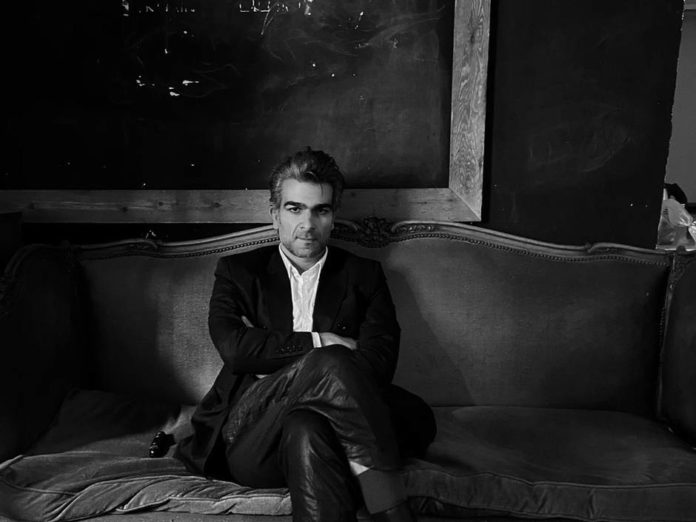

“I grew up with the knowledge that my grandfather was the first photographer of Gaza and one of the most important,” Djeghalian, an artist and academic, tells The National. “It was a given. Something I grew up hearing. But I never saw his professional photos until I discovered the negatives.”

They were not categorized in any discernible order. There were no accompanying materials dating them or listing the names of those photographed. But the clutter of film rolls was the closest Djeghalian had come to his grandfather’s work and adopted hometown, and were the most vital evidence of his legacy.

Djeghalian took them to Paris, where he lives, and began developing them. The photographs he chanced upon were shown to the public for the first time in March, as part of an exhibition curated by Djeghalian for Cairo Photo Week.