By Mark Arax and Aris Janigian

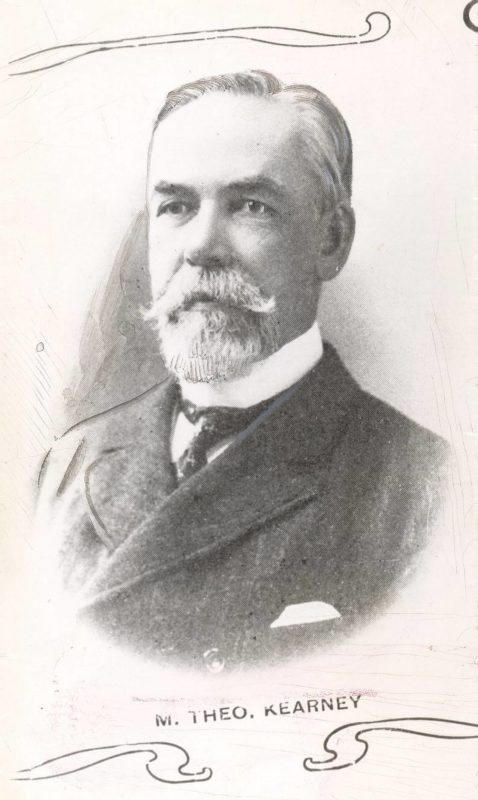

FRESNO (Fresno Bee) – We stood before the school board last week thinking it might be a good time to start a conversation about how Fresno became one of the most racially partitioned cities in the nation and how, as an outcropping of that history, there was an elementary school in the northwest part of town still named after a powerful white supremacist.

As authors whose books have uncovered the past, we knew the emotionally charged ground we were about to turn over. This was a dirt that grew everything. Burdened though our history was, we thought where better to begin a community’s education, if not its reckoning, than at the school board itself?

In the days before the meeting, we went to the county assessor’s office and found examples of the exclusionary real estate codes that for a half century had kept people of color from living beyond the ghetto.

Oddly, it had been no different for our tribe, the Armenians. Survivors of the 20th century’s first genocide, we had come to this Valley to start over, only to be forbidden to live freely by these same “Caucasian-only” codes. It did not matter that we were a people of the Caucasus, the original “white man,” you might say. In the estimation of official Fresno, which pulled every trick to keep us confined, first to the rural farm and then to the south side of town, we were “black Turks.”

As the two of us, shirttail cousins, rose up separately to address the school board and Superintendent Bob Nelson, we recited an especially vile paragraph from a real estate document dated July 20, 1939. On that day, a husband and wife finalized their purchase of a lot near First and Normal avenues. Among the restrictions they were forced to sign was this one: