After the collapse of the Soviet Union, when Armenia became independent, it considered its borders to be secure as a result of its military alliance with Russia. And Moscow, indeed, inspired confidence in its allies in the “near abroad,” considering itself the master of the Caucasus. It was also very convenient for Moscow that Iran was under Western sanctions, thus seeking friends and allies elsewhere.

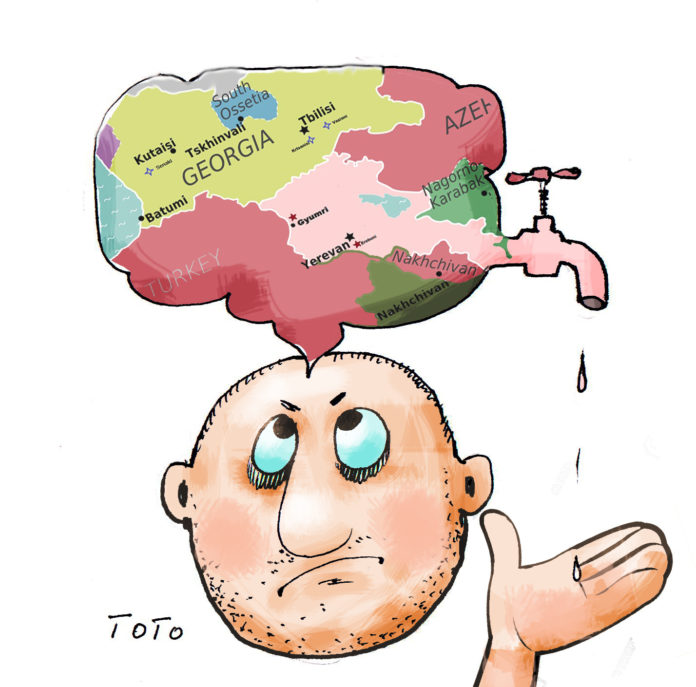

Both Turkey and Azerbaijan have ambitious plans in the region. Turkey’s goal is to drive a wedge between Russia and China, projecting its power in order to ultimately bring under its sway all the Turkic nations in Central Asia. Azerbaijan, on the other hand, has other plans for expansion, by integrating southern Azerbaijan — Northern Iran — and “Western Azerbaijan” — Armenia.

Despite their misgivings with both countries, the Western powers and Israel look favorably on these plans, if not even encouraging them.

Turkey was not a major factor or concern in the region until President Recep Tayyip Erdogan revealed his pan-Turanic, imperial ambitions and began testing Russia’s strength and resolve to hold its ground. And as all confrontations between Ankara and Moscow have demonstrated since — in the battlefields of Syria, Libya and Karabakh — Russia gave in to Turkey’s thrust and parry and settled for damage control. However, Turkey is pushing for more by arming Ukraine with its Bayraktar drones and questioning Russia’s legitimacy in Crimea.

Erdogan’s spokesperson, Ibrahim Kalin, even threatened that Turkey could cause Russia to explode from within, by activating the 25 million Muslims living there. The administration of Vladimir Putin has maintained an uncharacteristic silence, proving the potential truth of that threat.

Besides the 25 million Muslims, it looks as if Putin’s circle is also beholden to the Azerbaijan oil lobby in Moscow. Lragir.am reports that Azeri dictator Ilham Aliyev has funneled a $10-billion bribe to Putin cronies through a friend of the Russian president, Ilham Rahimov, to assure Armenia’s defeat in war.