“She had promised to kill the child as soon as it was born.” These chilling words begin Susannah Harutyunyan’s Ravens Before Noah, which was awarded the 2016 Presidential Prize for Literature. Born in 1963, Harutyunyan has published eight previous novels including Map Without Land and Waters as well as a few short story anthologies. A popular writer in Armenia, she also edits the literary magazine Kayaran. The underlying premise behind much of the action in this accomplished author’s present tale should intrigue anyone with an anthropological or sociological bent. Set in a small village in the Armenian Caucasus sometime around mid-century, novel describes the lives of a set of refugees from the Hamidian massacres of 1894. The residents of said village lead mostly sad and superstitious lives but seem happy enough. This in spite of the fact that they live under the protective watch of Harout who is a combination Godfather-enforcer. They sell their vegetables and fruit to surrounding villages and live constant fear: fear of being discovered, fear of the Turks coming back, fear of each other.

The main plot of Ravens Before Noah revolves around a child saved from certain death. Harout meanwhile grows up and falls in love with a beautiful young girl, Nakhshun, who suddenly arrives in the village one day, and who has been tortured and raped by Turkish soldiers. To complicate matters further, she is pregnant and so the village women plot to kill the twin girls whom she gives birth to. The amot factor plays a big role in this, given the humiliation that the Armenians have recently faced. But when she gives birth to twins, Sato the midwife — who will routinely kill a child in return for a sack of flour — cannot get herself to kill two children. It’s a strange code of ethics, but what the heck. Similarly when Harout dislikes a newcomer or someone in the village crosses him, he has no qualms about taking an axe to their head or having them dragged by a horse, eviscerating and tearing them to pieces on the pavement beneath.

Here is Harutyunyan at her best, describing Sato on horseback, sent on an unlikely errand by Harout: to dig up some human bone, grind it up and bake it into rolls of bread that they then feed to some scared newcomers in order to make them overcome their fear:

“The fear was there—the fear of the darkness, the cold, the fear of predators, but their fear of God did not bring them to their knees, for they were doing good deeds…She climbed on the Wild Horse and sped through the peace of the night. And the peace of that night was frightening—it consisted of groans, the screeches of hawks, the sighing of the wind drowning in the valleys, the crackling of the rocks pouring from the mountaintops…And Sato sped as she clung to the neck of the horse, unable to decide which side she should take. She had never been so afraid. She would have refused if it had been up to her. But the throbbing veins of the sweating animal vibrated beneath her calves, and vapor rose along the side of the horse from the heat they were generating and she was afraid that if she did not fulfill the command, the horse with the trembling flanks would drag her from a rope made of its tail hairs and shatter her bones against the rocks and nobody would bother to check when it was dusk whether it was her blood blackening on the stone or the sweat of the sun.”

While Harutyunyan is technically a realist writer, there is something mythical about her characters, so extreme are they. They have been deformed, stretched out, bent if you will, by history and by the veritably strange lives that their isolation and village ways have imposed on them.

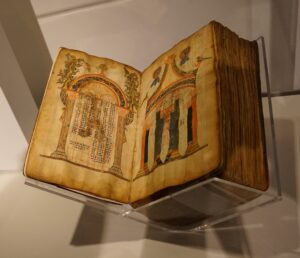

In my head while reading Ravens before Noah, images of a naïve or even baroque sensibility kept re-appearing. Naïve I suppose because this movement in the arts often depicts village life in simplified, picturesque scenery. In particular the paintings of the Tbilisi painter Gayané Khatchaturian kept recurring. Khatchaturian, who represented Armenia at the 2009 Venice Biennale was of course considered by many to be a naïve painter. But unlike say the Haitian (Ernst Louizor and Saincilus Ismaël) or Croatian (Emerik Feješ, Dragan Gaži, Ivan Generalić) schools of naïve painting, Khatchaturian’s work has something grandiose and overdone to it. The shapes are too large and almost super-human in their dimensions; and they seem expressionistic, even baroque in tone. In his recent book on the collaborationist dancer and choreographer Serge Lifar, The Fascist Turn in the Dance of Serge Lifar (New York, Oxford University Press, 2020), writer Mark Franko opposes the Baroque to the Neoclassical. The Neoclassical or Classical represents traditional ballet while the “baroque” embodies the counter-movements that it spawned: less rigid, more expressive of individual styles, if grandiose in presentation. This can of course be differentiated from the properly Baroque—a movement in the arts and music represented by practitioners such as Rembrandt, Bernini or Caravaggio. The dictionary definition of the movement is rather direct: “relating to or denoting a style of European architecture, music, and art of the 17th and 18th centuries that followed mannerism and is characterized by ornate detail.” Although Khachaturian’s work does not technically resemble the aforementioned painters, they do share many similar qualities. If you consider schools of painting and literature to exist on a spherical, non-linear spectrum then Haratunyan’s realism — like Khachaturian’s art — takes shape somewhere in between the wide swath that separates the two schools, naïve and baroque, if one can hold the two in one’s mind simultaneously.