By Dr. Talin Suciyan

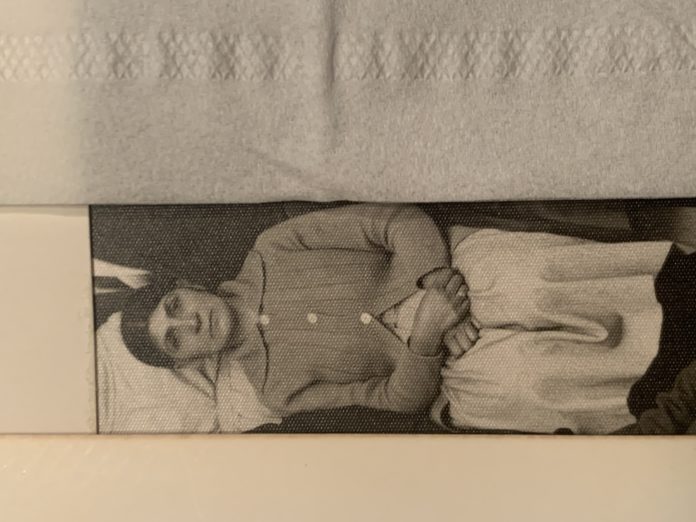

Herkan. She had one of those special names I had never heard before… It must be one of those old Armenian names, like the ones which I had only come across in the mid-19th century archival documents. She was the mother of four children and my admiration of her started when I got to know her one and only daughter. I had first met her daughter more than 25 years ago, when I was 16 and she was 48. We lost track of each other until reconnecting recently all these years later. I had not remembered her name, I had not remembered where I first met her, but I remembered how much I loved her. A heart full of love, which she inherited from her mother Fatma-Herkan. Now on the occasion of the 8th of March, I write to bring Herkan’s legacy into the present, as it whispers a long-lost song into our ears, one that we all recognize.

Herkan was born in 1919 in Dersim’s Kızılkilise (Red/Crimson Church) town. In those years, the village still had five churches, and its name has since been changed twice; to Nazımiye and Haydari. There were no Armenian schools in her village, and if there had been, it would not have been possible for her to attend. She had a sister she hardly knew, as they had been separated when Herkan was a baby. This sister Filor had been taken by their aunt when she left Turkey to seek refuge in Argentina. The sisters had to wait most of their lives until they were finally reunited there in 1961, where Herkan later settled and is buried.

Shortly after Fatma-Herkan was born, her village suffered a massacre. Herkan’s mother found a baby, Minas, still alive under the corpses. His parents had been killed, and so she breastfed him along with her own child. Once they were 15, Herkan’s parents did not have options for who to marry them to, so they were married to each other. There was no legal marriage in the village, so they were simply together and Herkan had their first child Yusuf-Arturo at the age of 16. A second son Mustafa later adopted the name of his father Minas. Herkan and her husband were together for 4 years until he died of hepatitis.

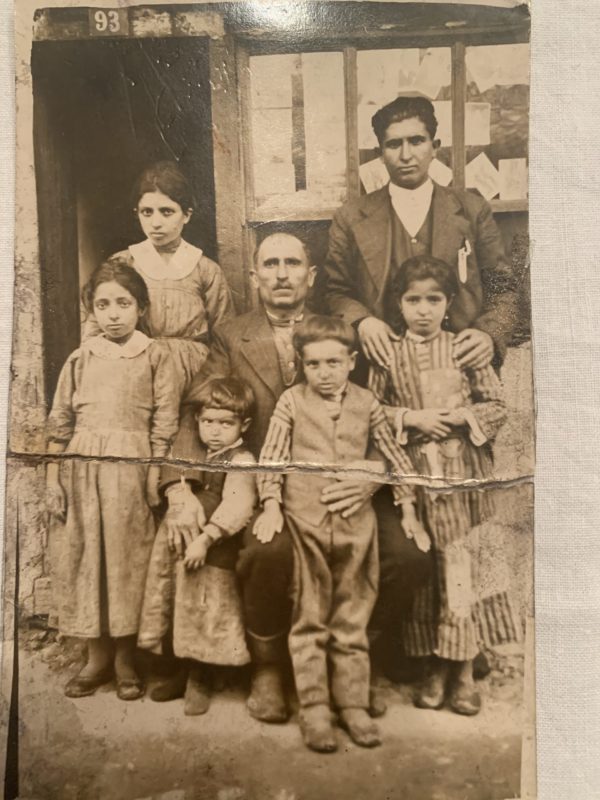

As Herkan’s father and husband were dead, she was in need of a male guardian and so needed to be remarried. She was sent to Kütahya with her two sons to meet the man who was to be her second husband, Ibrahim-Khoren, who had recently lost his wife with whom he had six children, three male and three female. He was an Armenian who had been exiled with his family from their hometown of Halvori in Dersim in 1938 after the massacres. They resettled in the villages of Küthaya, earning a living there through agriculture and animal husbandry. Khoren needed a wife to help care for his children. So were Herkan and Khoren married, this time legally.

Some of Khoren’s children were adults at this point, and his oldest son was just three years younger than his new step-mother. Herkan gave birth to two children with Khoren, making them a family of ten children. Ibrahim-Khoren worked in many trades, and was known as “şapigci Khoren” [Khoren the weaver] as well as “ironsmith Khoren,” a name still familiar to the Armenian families of Dersim. According to his daughter he was a brave, fearless man, and the villagers were afraid of him. He sent his three daughters to the school, which meant accompanying them back and forth every day in order to protect them from kidnapping. History repeated itself as Khoren too died at an early age. Thus, after a total of 13 years of marriage between two husbands, Herkan again found herself a widow at the age of 33, this time with ten children in the midst of a Turkish village with no relatives.