Karine Khodikyan’s deft prose accomplishes something quite rare: it plumbs the depths of the human psyche and presents moral quandaries in realistic ways without being didactic. Her wonderfully dark tales limn the boundary between reality and fantasy, the concrete and the fantastic. They recall the theory of the unheimlich or uncanny, defined as a character’s response upon encountering something that is at once strange and familiar — usually fear or apprehension. Khodikyan zeroes in on small family units or individuals and spins out from there, describing everything from simple male-female sparring between partners all the way to life-and-death encounters. Yet she never makes a final or definitive statement about an issue or person and often leaves things open ended, sometimes even turning things on their head at the very end. The result is evocative, sometimes scary, always interesting.

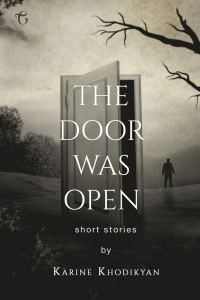

In the title piece “The Door Was Open,” a sexy insomniac thumbs her nose at a neighbor who is in a frenzy regarding a supposed half-naked serial killer who is on the prowl for single women in the neighborhood. Khodikyan sets the mood as the main character comes home and opens her apartment door: “But when she opened the door and the empty darkness of her corridor rapidly embraced her with greed, she would feel like she was growing acquainted with her own grave.” What a delicious if cold image: darkness that greedily surrounds and envelops you, as in your grave! Yet that very night the woman sees a man profiled against her wall who meets the description: naked above the waist, eyes shining like a cat’s. Does she imagine it? The man observes her (or does he?), and elicits physical responses from her—then disappears? In any case her fear is palpable, the event uncanny and inscrutable.

As in other pieces, Khodikyan cleverly leaves the answers up to the reader. Her constant ally: a wry sense of humor. When her frantic neighbor first insists that the woman take precautions, the main character asks deadpan: “Why would a serial killer come here?” (italics mine), as if there were no one worth attacking in her building or its surroundings. As in many of her stories, Khodikyan’s characters have no names: they are simply “he” or “she” or “the woman,” “the mother” or “my son.” The author thus universalizes her characters by simultaneously taking away this most important part of their identity.

The reader shouldn’t be surprised by Khodikyan’s mastery of her craft. She is a prolific writer and the editor-in-chief of the literary magazine Grakan Tert, a noted screenwriter and journalist as well. She’s served as the Republic of Armenia’s Deputy Minister of Culture and currently hosts the popular show “Between You and Me” on public television. In all these endeavors, one assumes that she is well served by her precise writing style and her ease at playing with conventions, as in the second story of this collection, “I wasn’t going.” What would you do if someone stabbed your only son to death and his mother then came to you begging for your leniency in court? Here the answer is: beat her down and try to tear her to pieces…But then the mother of the murdered child has a dream where it is her son who murdered the other woman’s child instead. The tables are turned: now what? The issue of whether one should one forgive at all, and if so when and under what conditions becomes more complex, unanswerable perhaps. For Armenians often obsessed with crimes from the past, this is an especially loaded question.

“Étude” is a deceptively simple look at the difference between the sexes, a husband who is constantly foiled by his wife’s superior verbal ability — Khodikyan’s version perhaps of Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus. The story opens with “‘See’ said the man’/“‘See’ thought the woman.’” By alternating between the unnamed man and woman, and between “I” and “she,” the author takes you inside the minds of both characters as they play a game of verbal/intellectual chess.

Death is a constant theme in the anthology. From “The Door Was Open” and the smell of the main character’s own grave, we move on to “The Smell of Bread and Death,” which features a family of hereditary gravediggers. We follow young Avet as he takes over from his father and learns to dig his first proper grave as he advances through the stages of his life. “Five Cars on the Road,” takes a tragicomic look at drivers who all speed by a man lying on the side of the road — but none stop to help him. In the ensuing arguments and accidents, one of the main characters is killed in an accident while another is murdered. Yet the ultimate humor comes from the man lying by the side of the road, who is just sunbathing it turns out. He gets up off the side of the road at the end and quietly walks away, the story now a parable perhaps about all those who fill their lives with constant and often meaningless events and encounters, mistakenly thinking that these will make them happy.