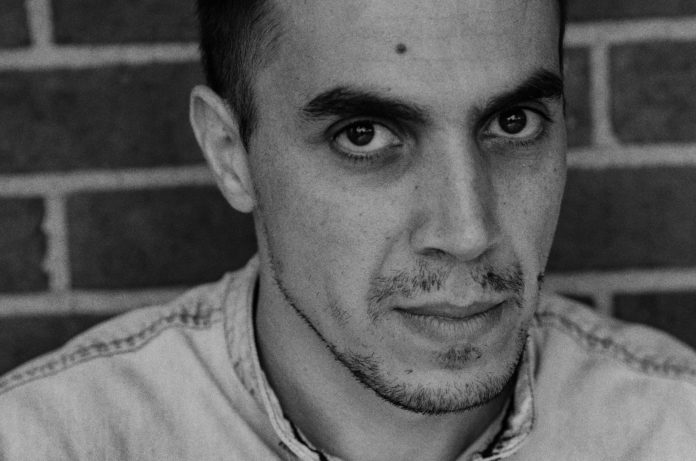

For a lover of the written word, nothing is more rewarding than discovering a new talent. Aram Pachyan is 37 years old, from Vanadzor, and studied law at Yerevan State. He is a columnist at Hraparak and writes the Lratvakan radio show. His first novel, the 2012 Armenian best seller Goodbye, Bird was turned into an opera with music by Arsen Babajanyan. Pachyan is raffish, sometimes sports a bandana over his chiseled face and has furrowed thunderbolts for eyebrows. He also writes extraordinary things. What does Pachyan write about exactly? Everything and nothing. Life and death. War and peace. Things at once large and small. In his latest book of short stories Robinson, this includes mean boys who plot horrid ways to dismember a retarded playmate; an alcoholic surgeon spiritually broken by war; and a young lad who takes a neighbor out on a date only to watch her get piss drunk and spend all of his money. He escapes out the bathroom window and rushes home to borrow money from his aunt in order to pay the bill. Many of us have been in similar situations. His are at once painful and comic sketches. One assumes many of the episodes to be autobiographical for their veracity and drama.

Born in 1983 in Soviet Armenia, Pachyan is the enfant terrible of post-Soviet Armenian literature. Is he a great stylist? Yes and no, not in the traditional sense. His sentences are short and declarative and so are the stories in Robinson, stuck somewhere between literary sketches and short stories. The pieces aren’t experimental or sensationalistic. Instead they derive their originality from a mix of stream-of-consciousness stylistics, a noir sensibility and larger-than-life characters. Pachyan writes about everyday topics, but doesn’t shy away from the tawdriness of things. In “Transparent Bottles,” a piece about alcoholism, the author describes what it feels like for a son to partake in a dubious chemical intervention with his mother: “My mother crushes a pill into the soup, the movement of her wrists are swift and agile. He quickly finishes his soup…(he) drinks a glass of water and goes to his room. I think, maybe he is gong to die, the pill will affect his blood circulation and his heart will explode. I feel sorry for him. Minutes pass. My father is uneasy. He rises from his bed and hurries to an open window; he’s short of breath. He’s gasping for air. He doesn’t know why he feels like this. There is fear is his eyes, the same kind of fear I have seen in the eyes of a street dog gnawing at a bone. My mother and I sit in the room with the silent patience of murderers. Father starts howling. We run to his side, lay him down to bed. The sheets stink of alcohol, his heart is throbbing in his chest.” ( P. 35)

Like the poet Violet Krikoryan, Pachyan lays bare parts of Armenian society often hidden from public view, as they often are in societies with conservative mores. Pachyan’s stories are also very Armenian, obsessed as they are with death, persecution, and tragedy but also presenting characters in love with life, always fighting, never giving up. The narrator quotes Narekatsi and one of his characters reads Khanjyan. Pachyan’s prose is steeped in the history of the land: Goodbye, Bird, the story of a 28-year-old returning from war, is of course especially topical today given the current Turco-Azeri war being waged against Armenia.

“Whenever my father upset my mother, I would go to Toronto…” So begins the short tale “Toronto” in which a young boy finds escape in the Canadian city of his mind, one that he has never visited in real life. The title story “Robinson” begins with an epistolary exchange between a fictional Robinson Crusoe and his man Friday before leaping into several gruesome tableaux, including one of school children slowly torturing and crucifying their teacher. In the three-page meditation on fear “The Suitcase,” a young boy goes on a mad search for dwarves that his father tells him lurk in a suitcase underneath his bed. The tale ends with one of the most stirring lines that I have read anywhere of late.

“Father Vilik” is ultimately the most satisfying of the stories in Robinson, if for no other reason than it has a happy ending. A young man visits a church to escape his father’s wrath after losing his job and thus ensues an unlikely friendship: “Father Vilik kissed my forehead. I took out an old lilac from the flower pot and gave it to Suzy. She was very happy. She said goodbye to me with her delicate fingers. The taxi left. Suzy had leaned her head on Father Vilik’s shoulder. Some loud laughter had been heard in the Vegetable District that day. The next morning, my father and I did not wake up.” (p.99)

The reader closes the book and thanks God for his own good fortune. Somewhere in Armenia a little Aram, now grown up, writes wonderfully sorrowful books and one hopes, no longer suffers quite so much.