BOSTON — By now, most readers of the Mirror-Spectator, particularly those who live in the Boston area have heard that oudist and singer Harry Minassian passed away this June. Amongst all the other bad news of the year 2020, the Armenian community lost a great artist. His obituary was duly noted in our paper and tributes have appeared in social media and other Armenian publications.

This writer never had the chance to speak with Minassian in person, and only saw him perform once — briefly. Therefore, to try to do justice to Harry Minassian’s memory, this writer contacted multiple musicians, friends, and family members to gain perspective on the life of a truly remarkable artist in the history of the Armenian-American community.

The Consummate Live Kef Performer

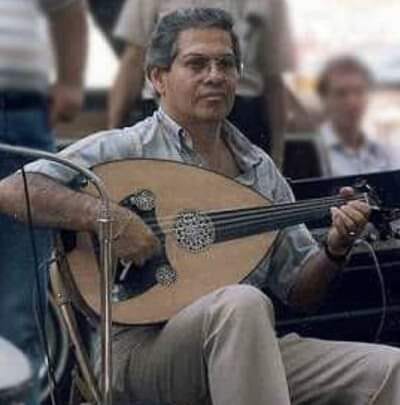

The first thing to say about Harry Minassian is that he was a consummate entertainer. More than one fan attested to the fact that more than almost any other Armenian kef musician, he had a seemingly innate ability to get a crowd going. Harry Minassian was an extremely talented and sensitive oud player. In fact, he took lessons from the legendary Udi Hrant Kenkulian himself, and was one of the five American-born Armenians to receive the title of “Udi” (oud master) from Udi Hrant in 1969. He was also a singer who played oud as he sang. His vocals seemed to hang in the air like a kind of mist which intoxicated his audiences. Somehow intense and gentle at the same time, his knowledge of Turkish as well as Armenian meant that he was able to put feeling into the lyrics that he was singing and make the audience feel them too, whether they understood the language or not. Although many artists sing and play the oud at the same time, Harry’s ability to do so was fluid and natural. Minassian was the Fred Astaire or Bing Crosby of kef music — he performed at the highest level of artistry, and made it look easy.

I spoke with one fellow musician who asked him to play at his wedding due to his renowned ability to work a crowd. The groom had to ask Harry in advance about how extensive his “Armenian set list” was because Harry was one of the last holdouts of the Armenian musicians who still performed predominantly in the Turkish language. Harry, always the gentleman, graciously handled the request to sing only in Armenian, but this was rather atypical for him. His agility with the Turkish language and his adherence to that repertoire is of course not unusual for Armenian-American kef musicians of his generation, but it was Harry Minassian’s specialty, and this fact makes a lot of sense if one knows something about his background.

Immigrant Beginnings