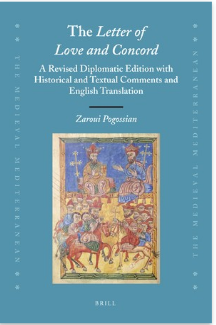

FLORENCE, Italy – Armenian studies generally is an individual scholarly pursuit in the West, with specialists coming together periodically for conferences and workshops. In Europe, this is suddenly about to change due to a major grant from the European Research Council (ERC), one of the most important funding bodies in the world, particularly vital for the humanities. Dr. Zara Pogossian has won support for a five-year collaborative project under her leadership focusing on medieval Armenian history in a global perspective. This appears to be the first time that a research project with a strong Armenological component has received such a prestigious grant from an internationally recognized body, as opposed to funding from Armenian institutions and sources. This will increase the overall visibility of Armenian studies in academia.

The ERC’s scale is very large. Its budget for 2019 was over 2 billion Euros. ERC grants are allocated through open competitions, and only approximately 12% of applicants are successful, with this percentage even lower for women. In Pogossian’s category of consolidator grants (for people who received their doctorate a maximum of 12 years prior to the application) in the social sciences and humanities, in 2019 out of 674 submitted proposals, only 78 were selected.

Pogossian’s grant is for two million Euros and she will be able to hire up to 9 researchers to work together. The project is entitled Armenia Entangled: Connectivity and Cultural Encounters in Medieval Eurasia, 9th – 14th Centuries (ArmEn), and will begin on October 1, 2020. ArmEn will be based at the University of Florence, Italy, where Pogossian is about to take up a tenured position as Associate Professor.

This position in essence, Pogossian said, would be an addition to the centers of Armenian studies in Europe. Even after the project’s end Dr. Pogossian will pursue her research and training of students at the University of Florence, continuing her already important contributions to Armenology in a most propitious academic environment.

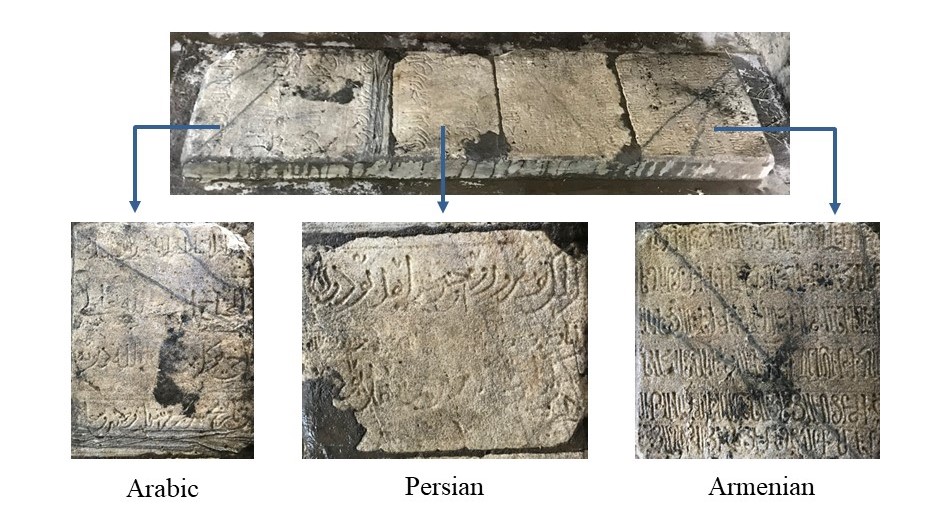

To indicate the scale of Armenian studies in general, she noted that when you have a conference of Byzantine studies, you can expect more than 1,000 participants, and when you have a conference in Islamic medieval studies, you can easily go beyond 2,000. Yet in the whole world there are only at the most several hundred specialists of Armenian studies in all time periods. Nonetheless, she stressed that this is a very important and strong field, even if it is a small one, with Armenian sources vital for topics in her period like the history of the Crusades, the Byzantine Empire, the history of Georgia, the Mongols, the Seljuks, and the Ottoman Empire.

The importance of the grant is multiplied when recent difficulties in academia are taken into consideration. Pogossian said that in the last 10-20 years it has been very hard to pursue small, sophisticated but highly specialized fields, find students, and then find funding for these students. Entire departments are scaled down by universities who say there are not enough students. This is true, she said, not only for Armenian studies but also for other Oriental Christian studies.