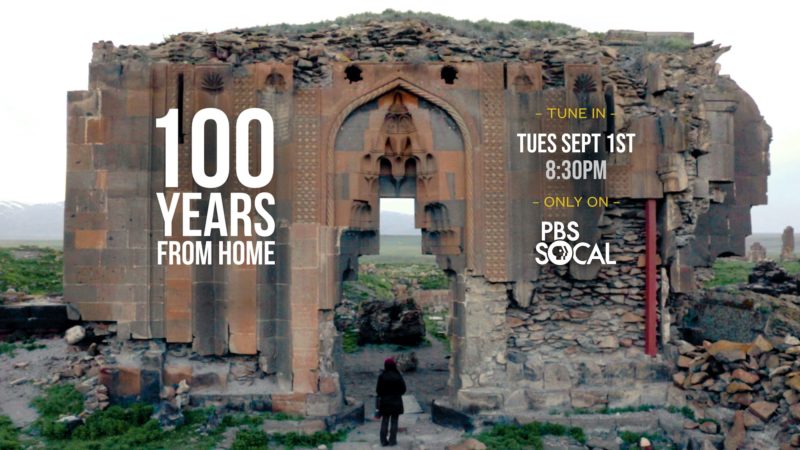

LOS ANGELES – The effects of the Armenian Genocide continue to ripple down through the generations, and a new film, “100 Years from Home,” provides more evidence for this. The film features the story of Lilit Pilikian, who is the great-granddaughter of genocide survivors from Kars, a city now in the Republic of Turkey. A documentary, it is a personal story bolstered with plenty of historical and cultural background, making it accessible to a non-Armenian audience, though perhaps even more moving to Armenians with a personal stake in this tragedy.

Pilikian is a first-generation American Armenian, who was born and raised in Los Angeles. She is an industrial designer by profession, so she needed the collaboration and support of her husband Jared White, who happened to be a filmmaker, to carry out this project. White declared, “It was definitely her idea,” while Pilikian jumped in to say, “but he agreed with it. My profession is to come up with crazy ideas.”

White had been working for a few years as a filmmaker. He had done mostly scripted films, shorts and web series, as well as commercials, and Pilikian occasionally helped him in a production design way. This was his first foray into documentary filmmaking. He said, “This was a kind of a departure for me, from my usual work, but it was something that was close to Lilit and close to me as well. It became a passion project that we both decided to pursue.” He suggested that perhaps Michael Arlen’s book Passage to Ararat, about Arlen’s quest to understand his Armenian identity, may have been in the back of his mind during the process.

Pilikian said that the centennial of the genocide played a big part in inspiring her to do this. She went to Armenian elementary school, and as a child participated in marches on the April 24th anniversary of the genocide, but never had been more actively involved in the issue. Growing up in the US, she felt caught between the Armenian and American cultures.

Some years ago, Pilikian helped take care of her grandmother Burastan Muradian toward the end of the latter’s life. Muradian’s family was originally from Moush, in Western Armenia, and had fled to Tsaghakasar, a village near Gyumri in Armenia, probably around 1900, where Burastan was born.

Burastan had preserved the blueprint or plans of her in-laws’ family house in Kars, a house that they had built themselves. Muradian’s mother-in-law entrusted it to her right before passing away. Pilikian said, “Every now and again she would bring it out and show it to me and say it was important to her. It was something she held onto till the end.” It represented the dream of going back home to their (interrupted) lives and homeland, Pilikian’s mother Mariam had said.