(Translated by Karen Jallatyan with editorial assistance by Alec Ekmekji; Marseille: Editions Thaddée, 207 pp.)

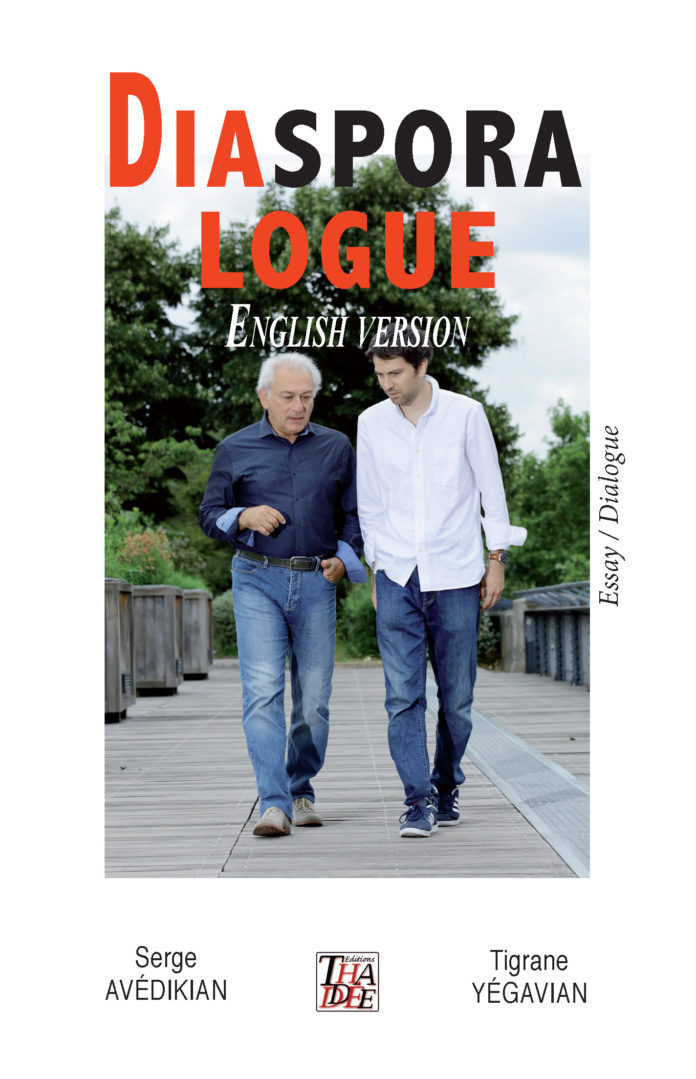

History often comes down to us in the form of memorized acts and dates or else completely fictionalized as literary discourse. So it’s a pleasant change to read a series of biographical dialogues between two incisive and successful members of the Armenian diaspora. Serge Avédikian and Tigrane (Dikran) Yegavian have both made their mark in French and French-Armenian circles, the first as a filmmaker and actor (Paradjanov, We Drank from the Same Water), the latter as a journalist and author of several books. (In the Shadow of a Sacred Mountain, Mission). In many ways their work is notable not only for its objective content but also for its ability to have mixed the French and the Armenian contexts and cultures with their own biographical journeys.

Much of what Avédikian and Yegavian discuss in the present volume is in a sense old hat — double allegiances, double cultures, double (sometimes triple) languages—but the personal stories that they interject here render these themes interesting again and gives them new blood. We learn for example that Yegavian’s father ran the Maison des Étudiants Français in the Cité Universitaire in Paris and moved to Lisbon to work for the Gulbenkian Foundation after a bomb exploded in his father’s office, a reaction it seems to recent ASALA bombings and the fact that the Cité housed a number of known ASALA members. Avédikian was born in Soviet Armenia to parents who had repatriated from France during the great reverse migration of 1946-47 known as the nerkaght or return before the family later returned to France.

To me the best parts of this book recount specifically biographical details, as when Avédikian recalls his life in as a child in Armenia: “Yes, I was the son of a repatriated foreigner; that is to say, they called me “François” to mark this fact, or sometimes, in a more vulgar way, akhpari d’gha ‘son of a brother’ (the word ‘brother’ was said with the accent of Armenians coming from outside, from diaspora, to mark the difference). We lived in a semi-basement of a building and the passersby saw what was going on in our apartment. My mother and her girlfriends smoked while drinking coffee, a tradition that is more occidental than oriental.” (p. 30)

Fascinating as well is the role that books and culture played for both: the Comte de Monte Cristo which Avédikian’s dad read to him as a child stands out, while in Yegavian’s case his formative years at the Lycée Français de Lisbonne provided a continuation of his own French identity and culture. Diasporalogue opens with a well-known quote from Nigoghos Sarafian about being thrown out into the sea of world affairs as an Armenian and learning to survive: and many of the scenes that Avédikian describes about his father’s existence in Marseille and the factories that Armenians worked in will echo in a welcome way scenes from Sarafian’s Bois de Vincennes, for example.

The book is divided into four parts in which Yegavian and Avédikian broach Armenian and Soviet history; Ottoman and Soviet legacies, as well as the meaning and ways of existing in diaspora at the turn of the 21st century. As in some other parts of the book, Part One (“The France of Our Dreams, The Countries of Our Childhood”) displays a tendency to ramble and to pat oneself on the back.