By Edmond Y. Azadian

Armenia attained its independence some three decades ago, and it has yet to find a way to successfully use that independence to further its goals.

Crisis after crisis have upset the country, hindering its economic recovery and forcing mass emigration.

The country is located in a very unstable region, requiring the utmost prudence to navigate through the extant political dangers. Additionally, two hostile neighbors are posing existential threats. Therefore, external dangers would have been enough to keep Armenians alert and ready to fight for their survival, but unfortunately, internal turmoil has come to exacerbate the situation. Currently there is extreme political polarization, in addition to the devastating impact of the coronavirus pandemic; the two have brought the country to its knees.

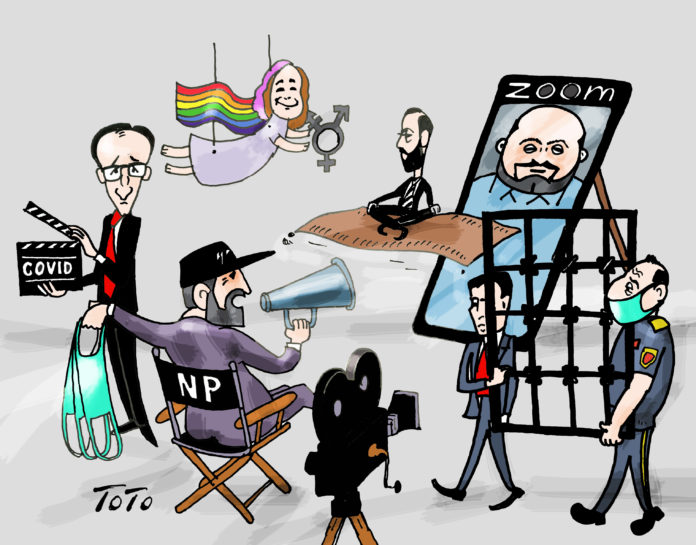

The Velvet Revolution, which took place two years ago, promised to end injustice and corruption in the country and to help it develop along modern democratic ideals. My Step, the party of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, which came to power with the support of 70 percent of voters, still enjoys an unchallenged popularity. Pashinyan himself promised to enforce “no vendetta” toward the previous regime. Yet, the momentum of the popular movement that he mobilized and rode to the country’s highest office, seems to have overwhelmed him.

In order to motivate his supporters in the current economic downturn, he has had to demonize the old regime and its leaders.