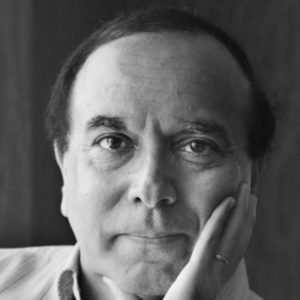

By Raffi Bedrosyan

This is a story told by Hrant Dink — undoubtedly, a true story. It can partially explain the deep trauma of the Armenians who survived the 1915 genocide but had nowhere to go and stayed in Turkey. It can partially explain the trauma of the hidden Armenians continuing to live in Turkey. And it can partially explain Hrant’s state of mind in the last few months of his life before he was shot dead — the constant persecutions, prosecutions and threats against him, his wife and his children.

The year was 1918, in a village at the foot of Suphan Mountain (Sipan Ler in Armenian, on the north shore of Lake Van). An Armenian youngster had barely escaped the events in 1915 and had found refuge in this village belonging to the tribal leader Ismail. He had mixed in with the other villagers, trying to eke out a living. He lived in a dark corner of a stable, in a crack between two rocks, just like a lizard that darts into the crack at the first sight and sound of danger. He would come out to help with the harvest or other errands, earn a piece of bread with his honest labour, then rush back into his refuge in the stable.

His name was Abdullah among the villagers, meaning ‘sent by Allah (God)’, but in reality, more like forgotten by God. He kept on living, unnoticed, uneventful – until one day when teenager Memo, tribal chief Ismail’s third son saw him urinating. Memo sprang up and started screaming while running to the village: “Run, run, come and see Abdullah’s dick. It has a cover on it!” Abdullah’s darting run back into the crack of the rocks in the stable was just like a lizard. Soon the entire village people had gathered in front of the stable, young and old. Stones started raining into the stable: “Come out, you infidel giavour, we know who you are, what you are. Come out!” The shouts and insults grew louder, footsteps started coming closer, and the stable door was opened. Chief Ismail tried to protect Abdullah and stopped the mob at the entrance. He talked into the darkness of the crack: “Abdullah, where are you? Come give me your hand. I will save you.” Ismail’s hand touched Abdullah’s hand or what he thought was Abdullah’s hand, but suddenly he was startled and jumped back. What he touched was a bloody piece of skin. He turned towards the mob and said: “Leave him alone. He is one of us.” Ever since that day, nobody bothered the newly ‘circumcised’ Abdullah.

Perhaps you have hunted lizards as a kid. Just when you think you have grabbed it, it escapes, leaving only his tail in your hands. In the villages and cities of Turkey, there were thousands of orphans and hidden Armenians who felt like lizard Abdullah, on a daily basis. But they learnt how to survive despite the trauma, because they learnt how to be resilient. One hundred years after the Armenian genocide, their grandchildren are now learning how to claim what is rightfully theirs – their identity, language, culture, and above all, truth and justice.