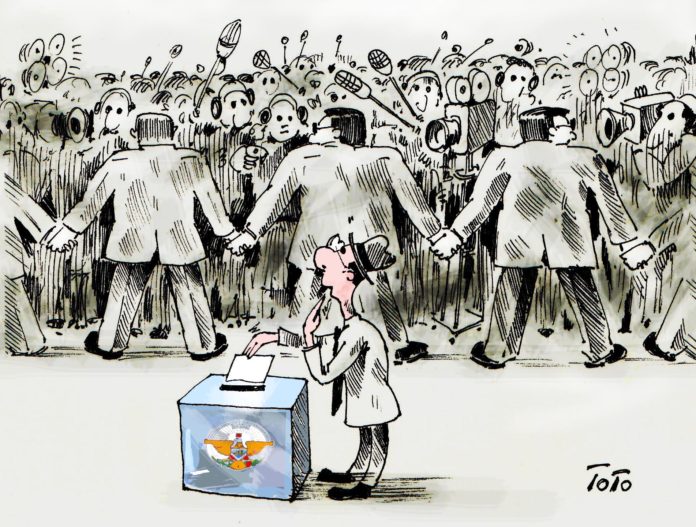

After much hesitation, pondering and debate, the elections were finally held in Artsakh (Karabakh) on March 31. These marked the sixth presidential and seventh parliamentary elections there.

The hesitations were fully justified, given the pandemic plaguing the globe. Miraculously, no case of coronavirus had officially been reported there until a week after the elections, with a first case on April 7.

Karabakh is a small disputed territory between Armenia and Azerbaijan, but it is located in one of the world’s political hotspots. Therefore, any action in that tiny enclave has an impact on the Armenian world, as well as on the regional and global spectrum. As a result, reactions from all quarters need to be brought into consideration to assess the significance of those elections.

There were 14 presidential candidates, 10 political parties and two alliances.

The numbers and the fragmentation of political groups were unprecedented. However, they indicated that democracy is on the move in Karabakh. The electorate was highly motivated, given the tense military situation in the region, compounded by the fear of the pandemic.

Many pundits had predicated a low turnout. They were all disproved as more than 73 percent of registered voters participated in the exercise of their political will.