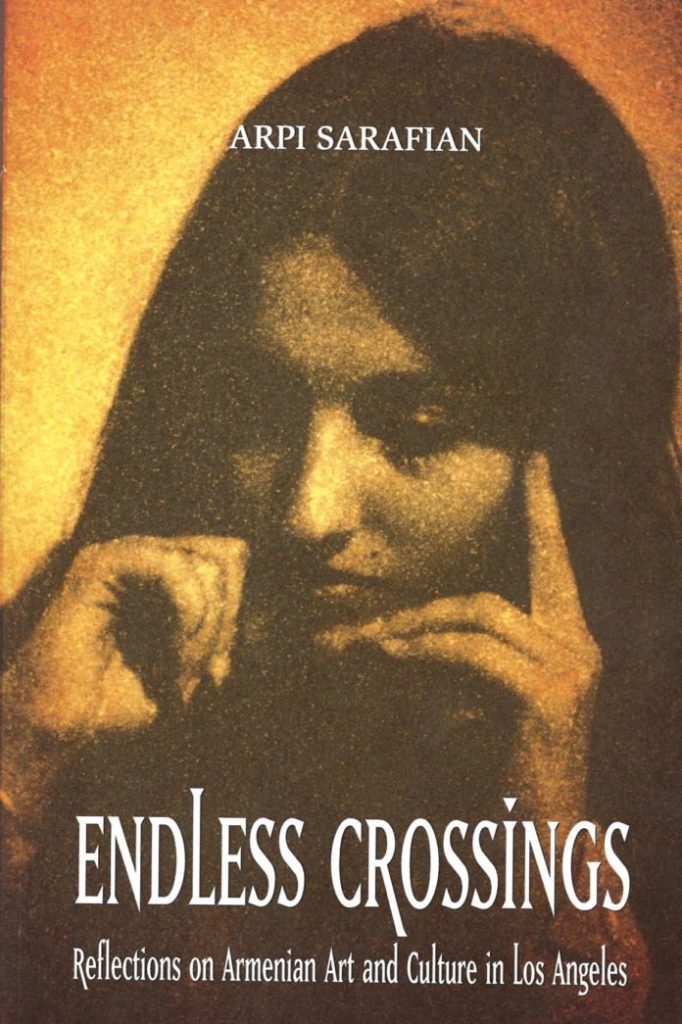

LOS ANGELES — In November 2019, authors Arpi Sarafian and Aris Janigian partook in an interview about Sarafian’s recent book of essays titled Endless Crossings: Reflections on Armenian Art and Culture in Los Angeles.

Janigian: These essays span thirty years, and cover everything from dance to literature to music to painting. You are one of the best and perhaps most important observers and chroniclers of our culture and its evolution in America, at least in recent years. Can you tell me over the course of three decades, how our accounting of ourselves through the arts has changed, if it has changed at all?

Sarafian: When displacement is a global phenomenon, our unique position of having been at the crossroads of histories and geographies for centuries becomes a great asset. Indeed, our ability to negotiate the diversity of traditions, lifestyles, and languages we find ourselves immersed in in the Diaspora is evidence of our evolution. To survive a culture has to evolve. The ultimate concern of maintaining an Armenian identity away from the homeland may remain unchanged but second and third generation artists seem to confront the challenges of displacement with a new openness. Some fiction writers take us into the midst of the horrors of our recent history of deportation and massacre unflinchingly. Others weave beautiful love stories into a dark chapter. Still others write about the challenges of settling in a new country, thereby making their creations relevant to an even larger community of immigrants.

An interesting recent development is the proliferation of more research-oriented publications. The hidden Armenians of Turkey, revolutionary parties in the Ottoman Empire, even cookbooks that preserve our traditional recipes, are attempts to keep our history and our culture alive, but only time will show their relevance. Further evidence of our efforts to prevail is the ongoing debate over the Eastern and Western dialects of the Armenian language.

We have obviously moved beyond victimhood. We do, however, still ask the same questions and provide the same answers. The Genocide is still our key point of reference. Memoirs and personal accounts of the massacres and the deportations abound. Playwrights also draw on our recent past for inspiration. Richard Kalinoski’s 1992 “Beast on the Moon,” a play about two young immigrants who escape the Genocide and start a new life in America in the 1920’s, or Aram Kouyoumjian’s more recent “Constantinople,” which focuses on the Armenian community in post-Genocide Constantinople, are good examples. It is perhaps true that one does not repeat the essential enough.

However, while the artistic output is impressive, I see little attempt to challenge ourselves by thinking more critically and transcending our (almost obsessive?) focus on the fear of extinction. An Armenian identity is certainly crucial but we could perhaps try to embrace more of what “others” have to offer so that, while still retaining our distinct identity as Armenians, we cease to exist as an entity apart. Existing within the framework of a multiplicity of cultures greatly enhances our efforts to survive, our ultimate goal.