By Harry Kezelian

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

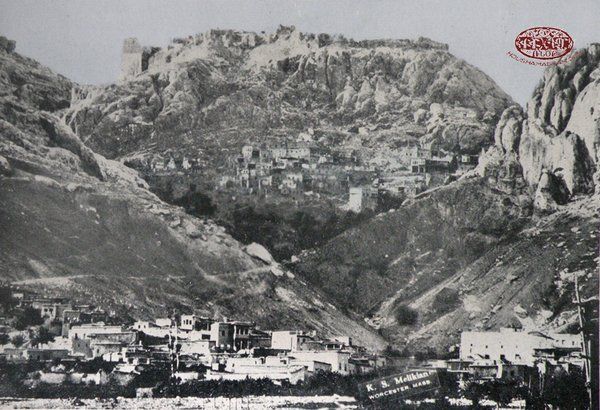

CHICAGO — The background image on my laptop is a panoramic photograph of the village of Husenig with its surrounding mountains and the city of Kharpert on the mountainside above it. The other day I was looking at this image as well as the image of the 1910 graduating class of the Getronagan Varjaran in Kharpert, which I have taped above my desk, and something in my head clicked as it never had before.

I work as a US History teacher in the Chicago Public Schools, but I am originally from Detroit. I have a fellow teacher, about 15 years older than me, Greek-American, raised in Chicago. One day he asked me, “have you ever been to Armenia?” and when I replied in the affirmative, he continued, “do you guys have a house there or some place you go?” I saw where he was going with this line of thought. Many Greek-Americans, particularly those with roots in the Greek Islands, have summer homes back in Greece, on an island – getaways where they can spend time in the summer with family, and reconnect with the inhabitants of not only their native country, but the very native villages from which their families came.

I had to explain to my friend that the situation was not the same with us. Armenian-Americans of Western Armenian descent do not have the luxury the Greeks possess, except for those from Istanbul and (until recently) Kessab. Our ancestral homes have vanished, our villages are populated by Turks and Kurds, and only in the last few years has it even become safe to go and take a look at those places. No one would dare buy a summer home in Kharpert or Sepastia — if the Turkish government would even allow it. And even if one could buy a home there — why would one go? To reconnect with the Kurds and Turks of our native provinces?

All of these points, I know, have been discussed and stated time and time again by thinking Armenians. Why am I repeating them? Well, I was looking at this picture of Kharpert, and as I said, something clicked.