By Harry A. Kezelian III

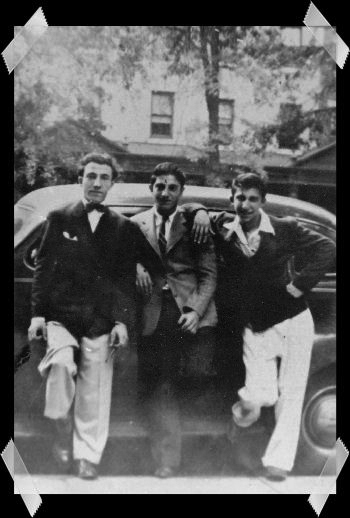

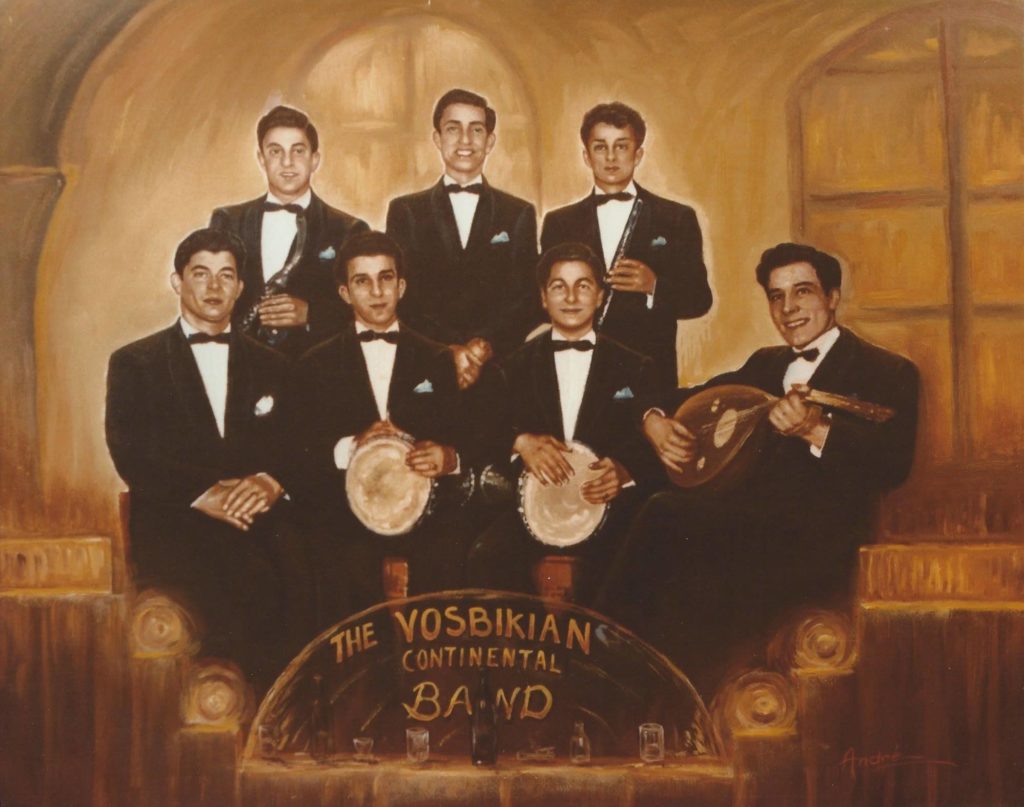

PHILADELPHIA — Eighty years ago, in 1939, three teenage Armenian-American brothers, Sam, Mike, and Joe Vosbikian, from St. Gregory’s Armenian Church in North Philadelphia, started a band with their two friends Charles Mardigian and Peter Endrigian. The Vosbikian brothers were the children of Genocide survivors Bedros and Vartanoush Vosbikian, and what they did truly marked a rebirth of Armenian culture in the Diaspora.

The “Fabulous” Vosbikian Band was the first Armenian band whose members were born in the United States. They were pioneers. They were the instigators of an entire movement. They were copied by many, but equaled by few. And in the nativist atmosphere of early-20th century America, what they did was bold.

Mike Vosbikian, the last living survivor of the original band, passed away Wednesday, August 14, peacefully, at his home in Medford, New Jersey. His death marked the 80th anniversary of the founding of the Vosbikian Band, and truly the end of an era.

It can honestly be said that the history of dance music in the Armenian-American community would not be the same without the Vosbikians. Unlike other immigrant ethnic groups in America, who turned their attention to Big Band Swing in the 1930s, the Vosbikians turned to Armenian folk music — jazzed up to their liking and to the enthusiasm of their young Armenian-American peers. Through them and through the genre they gave birth to — now known as “kef music” — the survival of Armenian folk dance in a social setting was secured in America.

Emulating the earlier immigrant-generation bands, such as Bernard Kondourajian’s Arziv Orchestra, which played at the picnics, weddings, and hantesses of 1930s Philadelphia, the Vosbikians played a combination of folk, popular, operetta, and both Western and Eastern Armenian tunes, with the true Western-Armenian beat that they learned from their parents’ generation, born in the town of Malatya in Kharpert Province. They gained popularity in their hometown and made their first out of town appearance at a 1940 AYF jamboree in Union City, New Jersey.