By Stephen Kurkjian

PARAMUS, N.J. — John A. Simourian was a legendary athlete at Watertown High School and Harvard College during the mid-1950s and his successes on the football and baseball fields made him one of the most celebrated Armenian-American sports figures in the 20th century.

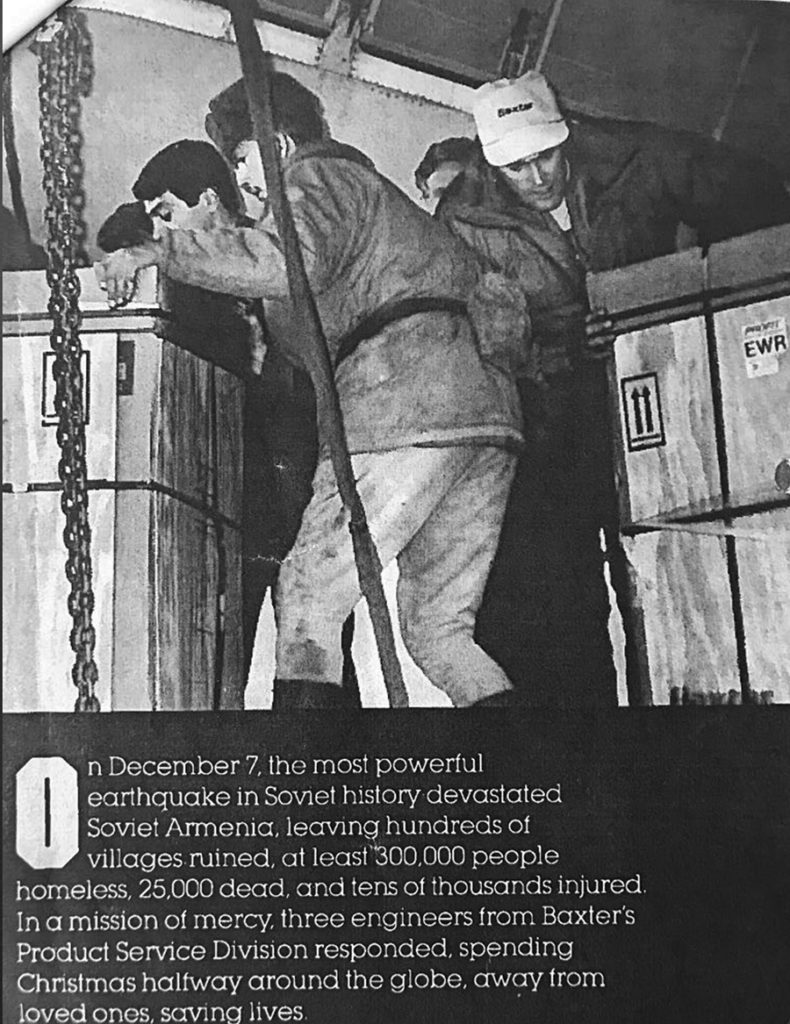

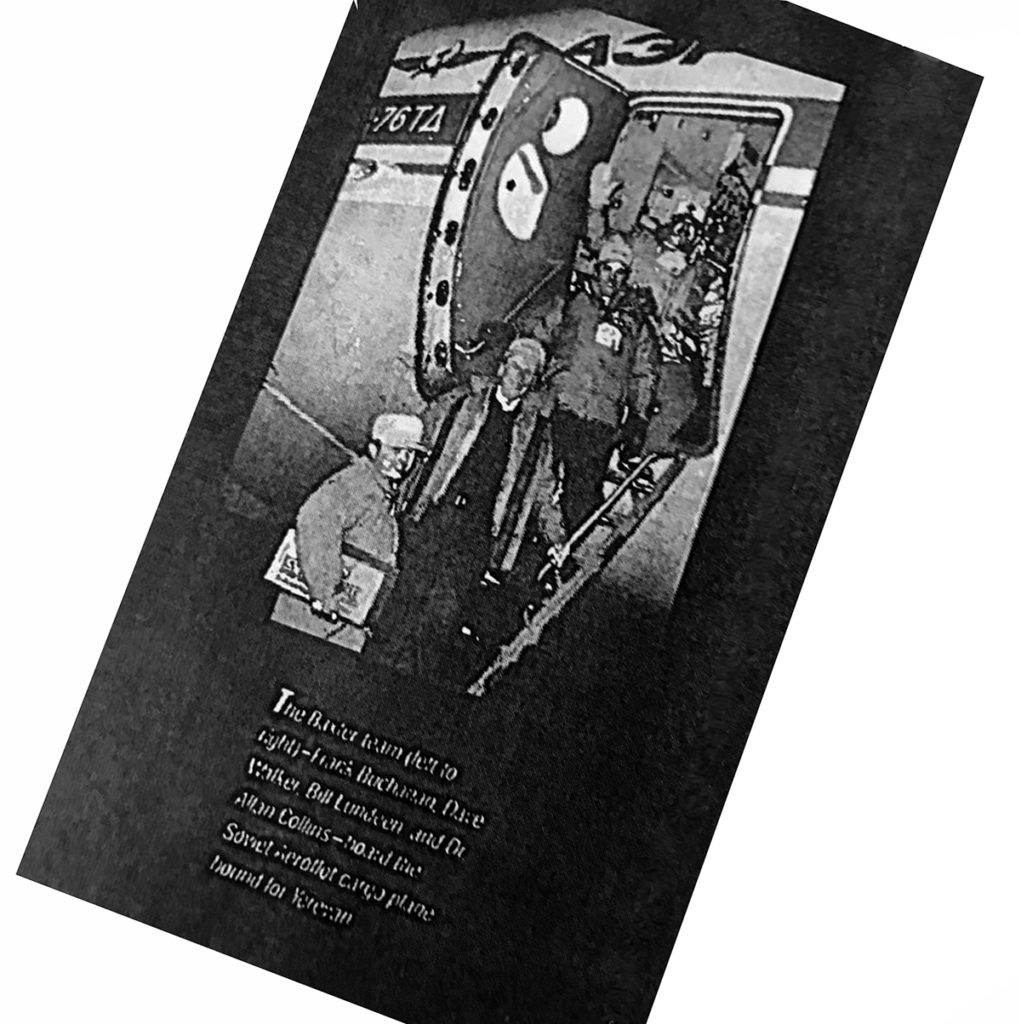

Yet unbeknownst to everyone except a few close friends, Simourian initiated a relief effort that saved the lives of numerous victims of the devastating earthquake in Armenia in 1988 by reaching out to two players he had met while leading Harvard’s football team 30 years before.

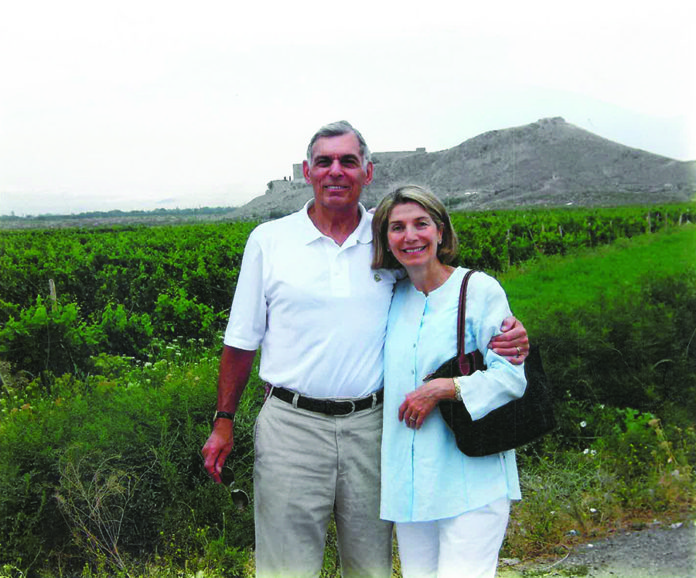

The relief effort, which depended on a secret agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union to succeed, was spurred by an entreaty to Simourian by his wife, Michele, that “we’ve got to do something” hours after learning of the disaster.

Three decades later, the devastating earthquake is a reminder of the horrific events that Armenia and its people has had to endure to survive through history. But a closer look of what followed it, particularly the collapse of Communism and the closer ties between those in the diaspora and the homeland, is also a tribute to the distinctly Armenian characteristic of not only surviving national tragedy but becoming stronger from it.

For Simourian, that journey began the morning after he learned of the earthquake. From his office as president of his family-owned transportation company, he called the chief of one of the country’s largest manufacturers of dialysis equipment, a man whom Simourian had competed against while quarterbacking Harvard’s football team and told him of the crisis.