By Lilit Sargsyan

Translated from Russian by Artsvi Bakhchinyan

Special to the Mirror-Spectator

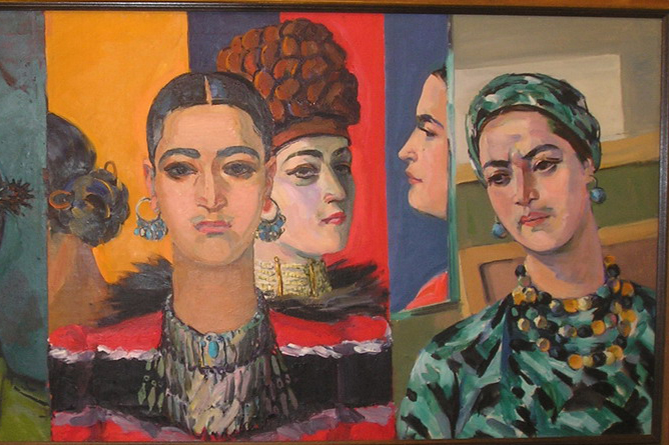

YEREVAN – When the creative image of an artist is deeply intertwined with her personal image, they merge into a single whole. Mariam Aslamazyan is presented in such wholeness. Her character, her life principles, contrary to all stereotypes, served her sole creed – art and development of her creativity. Nothing could stop this Soviet woman with Armenian patriarchal roots on her difficult and contradictory path, or even slow down her movement. From the stories and memories of the artist, it becomes clear that she grew up in a rather progressive and highly esteemed family and from early childhood she received those basic impulses and attitudes which raised her not just as a talented but as an independent, emancipated woman artist.

If we try to characterize her image briefly – both artistic and personal – it combines will and temperament, vital energy, exotics, and incredibly forceful beauty with power. Power and strength are masculine concepts, polished in Aslamazyan’s hands so aesthetically, as only a woman can do. The artist confessed: “I wanted so badly to be a man, but only one with a strong, hard character.” According to the eminent sculptor and artist Nikolai Nikogosyan, recently deceased at the age of 100 — to whom this confession of the artist was entrusted – “she possessed such a character.” Aslamazyan’s art stands firmly on the combination of strength and beauty, and these qualities characterize her image.

Aslamazyan’s painting is one of the brightest pages in the history of Armenian and Soviet painting of the second half of the 20th century. Her name is inextricably linked with the development of post-war and later – post-Stalin fine art. Like many Armenian artists of the Soviet era, fatefully connected to Russia, Aslamazyan also represents two cultures – Armenian national and Russian and Soviet. She was born in 1907 in the village of Bash-Shirak in the Kars region and spent her childhood there. From 1878 to 1917, this Armenian land, rich in cultural traditions, was a province of the Russian Empire, and in 1918, as a result of the politics of the First World War, it was handed to the Ottoman Empire.