By Alin K. Gregorian

Mirror-Spectator Staff

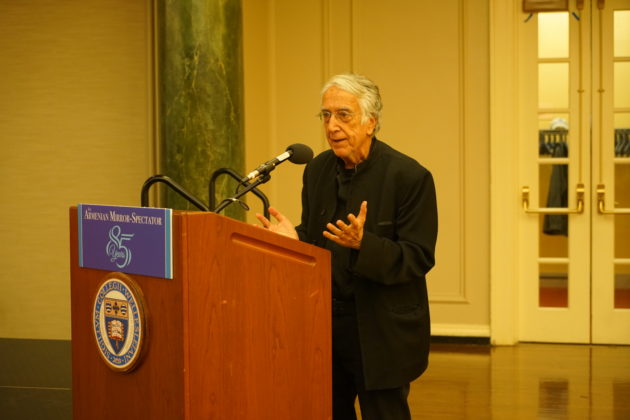

WELLESLEY, Mass. — The two-day celebrations marking the 85th anniversary of the Armenian Mirror-Spectator got off to a cracking start on Thursday, November 2, at a symposium on the lush campus of Wellesley College, at the Diana Chapman Walsh Alumnae Hall, featuring a panel of four exciting, world-famous journalists: Robert Fisk, David Barsamian, Philip Terzian and Amberin Zaman.

Armenian Mirror-Spectator assistant editor, Aram Arkun, also the executive director of the Tekeyan Cultural Association, served as moderator.

The theme of the evening was “Journalism and ‘Fake News,’” especially concerning the Armenian Genocide.

A standing-room capacity crowd of about 150 people was present for the program.