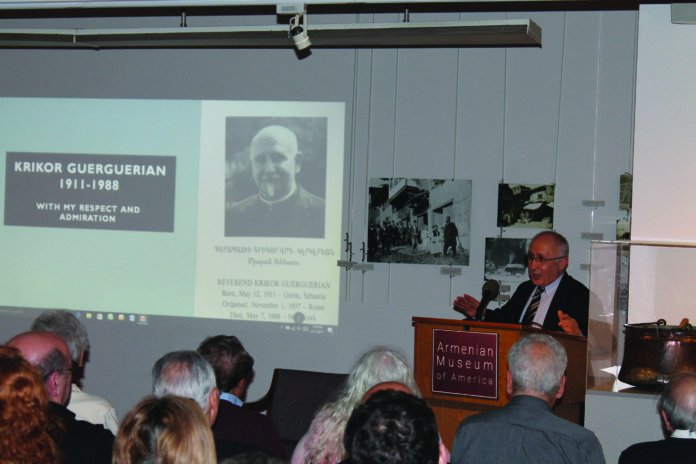

WATERTOWN — Prof. Taner Akçam presented a lecture with slides on the legacy of the work of Rev. Krikor Guerguerian on the Armenian Genocide, and announced the digitalization of the latter’s collection, at the Armenian Museum of America (ALMA) on May 11. There was a large audience present at this talk, titled “The Story Behind the Smoking Gun.”

Guests were welcomed by Michele M. Kolligian, president of the ALMA Board of Trustees. Marc Mamigonian, director of academic affairs of the National Association for Armenian Studies and Research (NAASR), introduced Akçam, who at present holds the Robert Aram and Marianne Kaloosdian and Stephen and Marian Mugar Chair in Armenian Genocide Studies at Clark University in Worcester.

Akçam dedicated his talk to the memory of Guerguerian, who was born in 1911 in Gürün, Sepasdia (Sivas). After witnessing the murder of his parents and surviving the Genocide, he collected materials to document its history for half a century. He died in 1988.

Akçam traced a direct line from Guerguerian’s work to his own by declaring that “the torch in the field of Armenian Genocide research was lit by Fr. Krikor Guerguerian and carried on by Richard Hovannisian, and most especially Vahakn Dadrian. I consider Dadrian my mentor and the founder of our field. I took over the torch.”

Akçam explained that Guerguerian embarked on his research career in 1937. Almost each year afterwards, he traveled to various countries, including Turkey, in order to collect materials. He used the penname Krieger when he published works, largely in Armenian. He also had an unpublished volume planned called Armenocide.

Akçam has been finding useful original documents in Guerguerian’s archival collection, now held by his nephew Dr. Edmond Guerguerian, a psychiatrist in New York City. This collection has been digitalized by Berc Panossian with support from a number of Armenians such as Hirant Gulian and Armenian organizations like the Jerair Nishanian Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and NAASR. Copies are held in a number of institutions, including the Armenian Genocide Museum Institute in Yerevan.