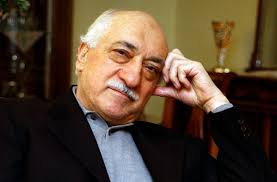

ISTANBUL (Guardian) — As the dust settled on an attempted coup in Turkey, a crackdown has ensued. Thousands of judges and soldiers have been detained and Turkish officials have vowed to “cleanse” a bureaucracy that they say has entrenched supporters of an exiled cleric, Fethullah Gülen, in positions of power.

ISTANBUL (Guardian) — As the dust settled on an attempted coup in Turkey, a crackdown has ensued. Thousands of judges and soldiers have been detained and Turkish officials have vowed to “cleanse” a bureaucracy that they say has entrenched supporters of an exiled cleric, Fethullah Gülen, in positions of power.

It is a hunt that the government fully expects the opposition in parliament to stand behind — now that their warnings and enduring paranoia over a coup by Gülenists have, they say, become manifest.

But how did it come to this?

The Gülenists once found common cause with Recep Tayyip Erdogan , supporting his Justice and Development (AK) party when it was founded on a realist, pro-European and business-friendly platform in the wake of a 1997 coup. They remained allies as Erdogan initiated peace talks with the separatist insurgency of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), and through the liberalization of the economy and EU accession talks.

“There was an overlap [with] Erdogan’s political party,” said a journalist and sympathizer of the Gülenist movement, also called Hizmet, who said he opposed the coup attempt but requested anonymity amid the tense political situation in Turkey.

Gülen’s acolytes were allies of Erdogan, partners in purges of the military over the last decade that turned into witch hunts, and ironically lead to the promotion of officers who would later take part in Friday’s attempted coup. Gülen’s supporters were instrumental in prosecuting two wide-ranging investigations and trials, known Ergenekon and Sledgehammer affairs, targeting “deep state” structures that were accused of planning to remove the AK party from power.