By Edmond Y. Azadian

Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night agitated by a nightmare where I see a million-and-a-half skeletons dancing restlessly and seeking a peaceful place to rest. An entire nation was doomed to extermination and believed to have been buried in 1915. But the skeletons are still dancing and they are still seek- ing closure for their brutal deaths.

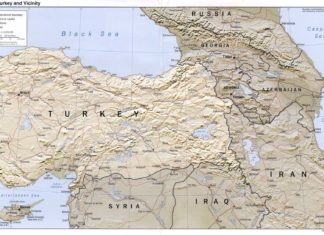

While the world turns a deaf ear to the pleas of those unburied bones and while Mr. Erdogan complains to Mr. Obama during their March meeting in South Korea that he is “bored” by the continuing attempts of the Armenians to have the Genocide recognized, we were hoping against hope that finally a resting place for the memory of those restless souls had found its place at a Genocide museum, within the walking distance of the White House at the nation’s capital.

The story was too good to be true. A few selfless benefactors had come together, pledged millions of dollars, bought a historic bank building to convert into a museum dedicated to the Armenian Genocide, thumbing their noses at the Turkish government and sending a political message to the world — stand- ing for justice, truth and commemoration of the martyrs.

It was indeed a historic moment as the centennial of the Genocide was around the corner and Turkey was already planning its pre-emptive strike to blunt the political impact of Armenian activism, in the most visible spot in the world.

The initiative itself was significant in the sense that it presumed some political maturity on the part of Armenians, as a few well-meaning individuals had come forth to realize this most challenging project. Many similar major projects in this arena in the past were stillborn when left to languish in committees who could not carry out the work.