By Edmond Y. Azadian

The Jews have come up with the definition of the “Righteous Gentile” to honor those non-Jews who have saved Jews during the Holocaust. One such towering person was Raoul Wallenberg, a Swedish humanitarian, stationed at the Swedish embassy in Hungary, who extended protection to hundreds of thousands of Jews marked to be dispatched to the concentration camps in Auschwitz, and thus he saved tens of thousands among them.

He became the pre-eminent “Righteous Gentile,” who ended his life in a Soviet concentration camp, after being captured by the Soviet troops occupying Hungary at the end of World War II. By the way, 2012 marks the centennial of Wallenberg’s birth, which is being celebrated worldwide.

Has the time arrived for Armenians to profile “Righteous Turks” who have helped some Armenians to survive during the Genocide? Is it time to honor Turkish scholars, journalists and political activists who have been struggling courageously for the recognition of the Armenian Genocide by Turkey?

Many apologists and some credulous Armenians rush to the conclusion that Armenians have to recognize these acts of courage by individual Turks.

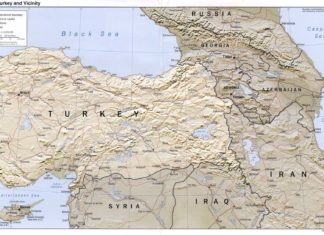

The Genocide was planned to devastate the Armenian nation, to scatter the survivors around the world and desecrate its historic homeland. After almost a century, Armenia’s survival remains a big question mark and Turkey’s continual blockade is nothing but its age-old genocidal policy implemented by successive regimes in Turkey.