By Muriel Mirak-Weissbach

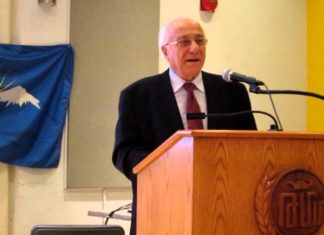

n 2005, the German Bundestag passed a resolution calling on the German government to facilitate a process of Armenian-Turkish understanding and reconciliation. Now, six years later, scholars and civil society activists are asking: what has been achieved since then? This was the subject of a one-day seminar on “The Armenian Genocide and German Public Opinion” on September 22, organized by the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Berlin. That all-party resolution called on Berlin to contribute to such a process by encouraging an honest examination of the historical record. This included demands for the release of historical documents both from the Ottoman archives and copies of documents given by the German foreign ministry to Turkey and the establishment of a historians’ commission with international experts. The aim was to encourage the Turkish authorities to deal with the 1915 Genocide and move towards reconciliation and normalization of relations with the Republic of Armenia. Guaranteeing freedom of opinion in Turkey, especially regarding the Armenian question, was stressed.

International historians presented updates on the status of genocide research: Prof. Raymond Kevorkian of Paris gave an overview of the history of genocide studies; Swiss historian Hans-Lukas Kieser and German researcher Wolfgang Gust discussed the German role on the basis of official documents and considerable discussion revolved around whether the Germans, allied to the Young Turks in World War I, were co-responsible or complicit, what they knew when and what they did or failed to do to stop it. One important point made by Gust was that, contrary to official Turkish propaganda that the Armenians constituted a military threat to the Ottomans, the German archives do not support this assertion.

The seminar then heard reports by civil society activists involved in engaging members of the Armenian, Turkish, Kurdish and German communities in a dialogue process about their common tragic past. Among the initiatives mentioned were the Hrant Dink Forum in Cologne (and now Berlin), the Association of Genocide Opponents in Frankfurt, the well-known study excursions to Berlin organized by Turkish-born German author Dogan Akhanli and others of Recherche International in Cologne and the grass roots movement of Toros Sarian, an Armenian journalist and editor from Hamburg who publishes the online magazine ArmenienInfo.net.

If such grass-roots initiatives have contributed significantly to educating citizens about the Armenian Genocide, there remains much to be done, especially on the level of formal education. Here, the issue of history textbooks becomes critical.

In Germany the state governments are responsible for curricula, but so far, only Brandenburg has succeeded in presenting the Armenian Genocide to pupils in history classes. Opposition to such teaching by informal Turkish lobbyists has thus far prevented other states from addressing this subject, among other controversial issues.