The following is a speech that writer Peter Balakian delivered at the National Center for the Book in France earlier this fall on his book, Armenian Golgotha, the memoirs of his great-uncle, Bishop Grigoris Balakian.

MARSEILLES, France — First I want to express great thanks to the National Center for the Book for making this week-long Armenian writers festival possible. It is an impressive part of the French government’s commitment to culture and intellectual life (I wish we had such an institution in the US) and affirms the importance of the book as knowledge and artifact, and as act of imagination and scholarship, and it celebrates the book as primary vehicle in bringing people and cultures together across the planet.

For this festival which you have so aptly-called Arménie-Arménies, I’m grateful for your bringing together the complex Armenian Diasporan culture in its 21st century form. And I’m grateful to France for valuing the Armenian intellectual voice and the richness of Armenian history and culture, and the richness of that history between Armenia and France. I’m delighted to be with so many Armenian writers from the Republic and from around the world, as we make this trip together for the next week by train to various cities, ending in Paris on the weekend.

I want to thank the Armenian communities of Marseilles for their hospitality and St. Sahag and Mesrob Cathedral for hosting me, and to Father Dertad of St. Thaddeus church for taking me and my wife Helen and brother Jim and aunt Lucille to Bishop Balakian’s tomb at the St. Pierre cemetery, and to Sahag and Mikael Karalekian of the AGBU for their hospitality.

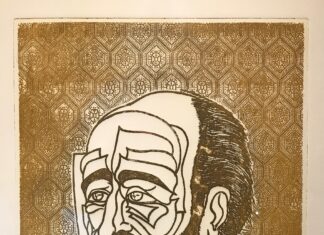

It is of deep personal significance for me to be here with you tonight. In coming to Marseilles for this Armenian cultural celebration in France, and for the recently published French edition of my memoir Le Chien Du Destin [Black Dog of Fate], I am also making a personal and familial pilgrimage to the site of my great-uncle Bishop Grigoris Balakian’s life and work — during the final phase of his career as an international figure among Armenian clergy in the first part of the 20th century, and as a leading Armenian writer and cultural figure.

Under the directorship of Bishop Balakian, the entire cultural foundation of the region of southern France was planned and built during those difficult years following the Armenian Genocide in the 1920s and ’30s. Out of the ruins of lost historic Armenia, Bishop Balakian had as his central vision a rebuilding of Armenian culture here where he was assigned as prelate in the late 1920s. This passion to rebuild Armenia is expressed repeatedly in his memoir Armenian Golgotha — even during the death march experience, the idea of Armenia emerging out of the ashes as he put it, “like the phoenix,” kept him alive through despair and anguish.